Game Over, Restart?

A growing wave of video games is going beyond pure entertainment to help us understand our place in a biodiverse world. What can we learn when we play along?

Video games are a potent but perhaps unexpected avenue into more-than-human design. As computational and graphical power have increased, the designed worlds of games have grown more detailed and more expansive. Less anthropocentric and more eco-centric worldbuilding, however, does not inevitably follow from vastly more polygons and processor cycles. Nearly all of the games featured in this visual essay were produced by independent artists and small studios. Their games differ markedly in aesthetics, duration, genre and tone, but all of them promote a kind of multispecies curiosity; an interest in how the world is experienced by creatures and entities that are decidedly not us.

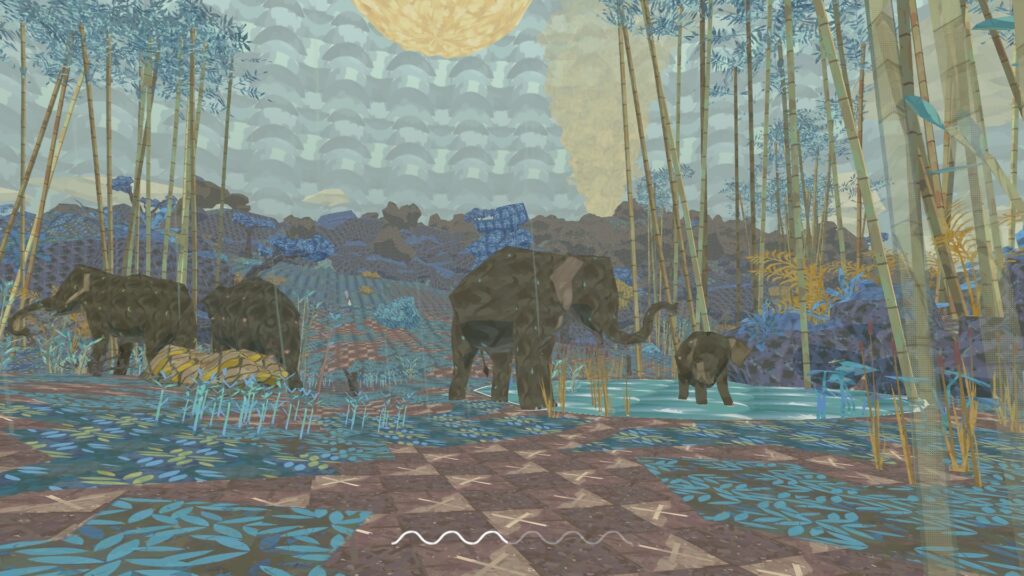

Unlike some techno-utopian games where humans are the agents of climate salvation, several of the titles in this essay envision postapocalyptic futures where humans are either entirely absent, such as in Stray, or mutualistically indebted to a non-human host, as in The Wandering Village. Many foreground animal, plant and even geological perspectives: the symbiosis between Joshua trees and yucca moths in The Alluvials, the meandering of an Andean river valley in Argentina in Atuel. Often, these experiments in making playable non-human protagonists speculate about the unique capacities of other beings, from an elephant mother’s ability to draw on ancestral memories (Shelter 3) to a landform’s stray thoughts in deep time (Mountain).

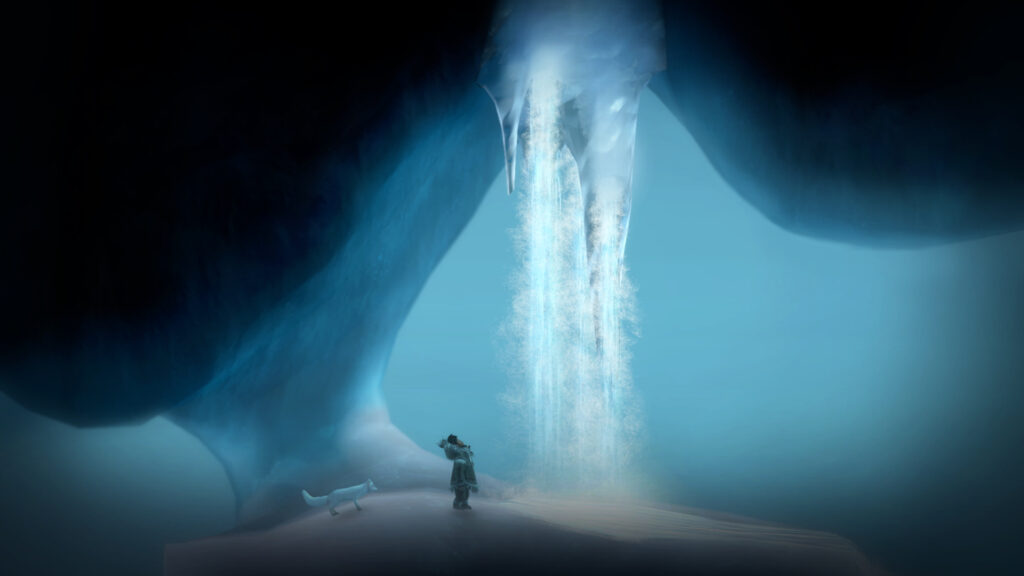

These games also reinvent classic game genres like first-person shooters (The Alluvials), city builders (The Wandering Village), survival games (Shelter 3) and platformers (Never Alone). In Never Alone, for instance, gameplay is shared between an Iñupiaq girl and an Arctic fox, platforms can be inert objects but also summoned spirits and the Arctic landscape is not passive scenery but the awe-inspiring manifestation of otherworldly forces. In The Wandering Village, Shelter 3 and Stardew Valley, survival is not just a matter of individual persistence but wholly dependent on fostering social and ecological community. Games like Luxuria Superbia, The Alluvials and Mountain also unapologetically remap the norms of player success away from mastery and comprehension toward something humbler, like a sensuous investment in the gratification of other species.

Advances in computation and graphical processing are not entirely without merit, of course. Games today can render the specificities of place and planetary biodiversity with sometimes astonishing accuracy, from the exotic marine species of Abzû to the garden varietals of Pikmin 4. Yet even without a surfeit of hardware, games are increasingly expanding beyond the confines of domestic and commercial space, aided in large part by mobile devices. As they inevitably accompany us on our way to work and school – even in the outdoors – we can allow them to draw our attention outwards, to consider more of our earthly neighbours and our interconnected outcomes. We can insist that future mixed realities be as playful, poignant and wondrous as these games imagine.

In Abzû (Giant Squid Studios, 2016), the Diver brings life back to moribund parts of the ocean while exploring the remains of a once great civilization. The Diver can also meditatively commune with the animals around her, like the various parrotfish, tangs, lyretails and damselfish seen here.

The Alluvials (2023) is artist Alice Bucknell’s queer ecological take on climate crisis and non-human agency in the Los Angeles River basin. In the ‘Extinction Burst’ level shown here (which Bucknell labels a ‘first-person pollinator’), you can alternately play as a flowering Joshua tree or its symbiont, the yucca moth.

Traverse the Atuel River valley of Argentina as a cloud, fish, bird, fox or the river itself, while learning about its historical, ecological and cultural significance in the 2022 documentary game Atuel from the Latin American independent game cooperative Matajuegos.

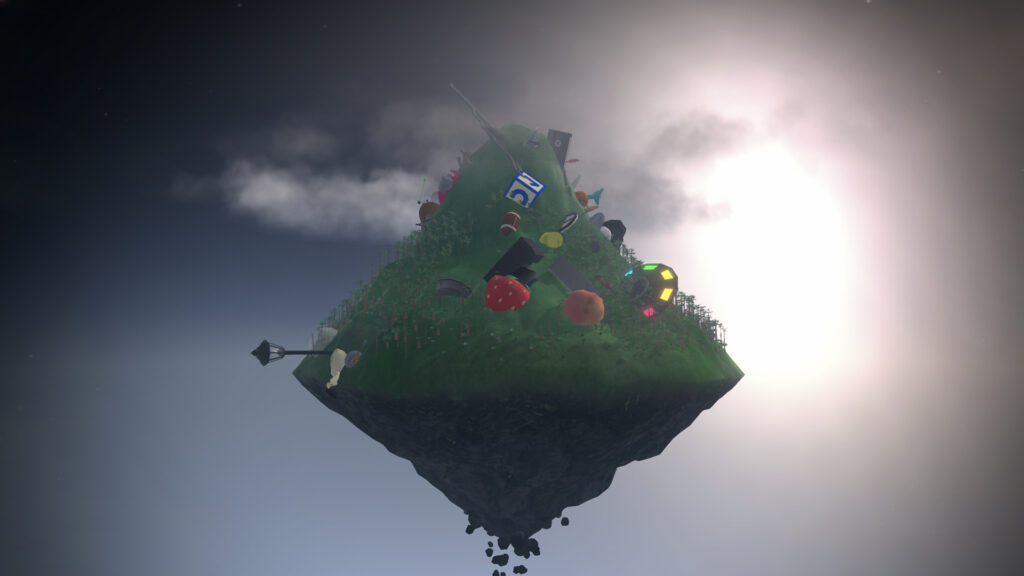

Many people questioned whether or not David OReilly’s Mountain (2014) was more game or toy, but its snow-globe-like invitation to watch, play and ponder in pseudo-geological time makes it a classic in more-than-human design.

Never Alone (E-Line Media, 2014) was justifiably lauded as the first video game created in close collaboration with an Alaskan Native people. The influence of Indigenous Iñupiaq culture and language is present in many forms, including art (scrimshaw), narrative (traditional folklore) and gameplay (the vitality of Arctic animals, terrain and weather).

Game studio Might and Delight is known for its Shelter animal survival games, which each feature a mother of a particular species as the main playable character. In Shelter 3 (2021), you play as Reva, a female elephant who must safely guide her herd to a rendezvous with the herd’s ancestors.

Only traces of humanity persist through the robot culture depicted in Stray (BlueTwelve Studio, 2022), a game in which a delightfully resourceful feline protagonist (with his drone helper B-12) tries to get back to the surface world after falling into an abandoned subterranean city.

The Wandering Village (Stray Fawn Studio, 2022) retools the city-builder genre by placing the human survivors of an environmentally calamitous world on the back of a giant beast (Onbu) who walks and swims from biome to biome. Players must see to the needs of both villagers and Onbu, while also earning Onbu’s trust and anticipating changing and often hostile environmental conditions.