Reading Saito in Kagoshima

Environmental economist Kohei Saito is already changing the way we think about degrowth and climate breakdown. How might his thinking be applied at a neighbourhood scale?

What would a society based on bioregioning feel like? What forms of economic growth might support bioregionalism? And where would we look for clues of alternate futures emerging?

Kohei Saito is perhaps an unlikely guide to such possible futures. Drawing from recent research into Karl Marx’s previously-overlooked environmental writing, Saito’s recent book Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto (2024) has propelled the author into as much limelight as it’s possible for a philosophy professor to receive. 1 Kohei Saito, Slow down: The degrowth manifesto. Astra House, 2024 For Saito has transformed historical analysis into an engaging case for radical societal change, driven by the multiple interconnected crises we are living through. Although degrowth is Saito’s stated mission, his work may also help prepare the ground for a commons-led bioregionalism.

Slow Down is a convincing story of extractive capitalism, colonialism and climate breakdown, and is as deeply referenced as you might expect. Saito shines new light on the works that bookend Marx’s writing, his marginalia and off-cuts, revealing that ‘metabolic rifts’ still course through our widespread biodiversity degradation. Similarly, the paradox that William Stanley Jevons first articulated in 1865 – that more efficiency leads to more resource use not less – now returns to explain why blunt technology-led ‘green deals’ will not work. 2 William Stanley Jevons. The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines. Macmillan & Co., London, 1865 In other words, we simply do not have the resources for mass electricification – of vehicles, appliances, energy – just as we have no evidence of any ‘absolute decoupling’ of emissions growth from economic growth. His conclusion is that only in a deliberate and equitable slowdown, within a new economics based on ‘reclaiming the commons’ and diverse forms of bioregional value exchange, do we find a meaningful, thriving future, oriented around a ‘radical abundance’ rather than an artificial scarcity. As Saito writes, cheekily appropriating Thatcher, ‘there is, in fact, no alternative’.

Yet the problem with Slow Down does not lie with the analysis (why things are how they are) but rather, with the synthesis (what they could be instead). For instance, this sentence of Saito’s may be broadly accurate: ‘Since capitalism is the ultimate cause of climate breakdown, it is necessary to transition to a steady-state economy’. But it is immediately followed by this one: ‘All companies therefore need to become co-operatives or cease trading.’ Really? It may or may not be difficult to imagine the end of capitalism – there are many versions of that out there – but it is quite hard to imagine, say, Apple as a cooperative. Saito’s language often appears a little too certain which, ironically perhaps, renders his proposals unconvincing. Saito has an ear for the aphorisms but not much of a hand to sketch out the details.

It is design’s task to help close the gap, just a touch, between ideas and things. In this respect, Saito’s vantage point is particularly interesting. Japan is effectively the first major industrialised nation to reach deep into the population slowdown, due primarily to social and economic shifts rather than an environmental one. This ‘population degrowth’ must relate in some way to other forms of degrowth. Indeed, Nomura Research Institute predict that at least 30 per cent of households in Japan could become vacant by 2033 which is, admittedly, one way of achieving low-carbon homes. 3 Wataru Sakakibara. What to do about the vacant house problem in Japan? Nomura Research Institute Journal, 20 April 2017. Source

But far from sliding towards it, Saito describes his version of degrowth as a ‘grand plan to transform the economy to a model that prioritizes the shrinking of the economic gap, the expansion of social security and the maximization of free time, all while respecting planetary boundaries’. Of course, he sees no sign of this in Japan’s official national policies and innovation priorities like their science-led ‘moonshots’ programme. He concludes, ‘Japan is far from being in a “leadership position” regarding degrowth. All that’s happening is capitalism’s long-term stagnation.’ Saito says this will lead to ‘the “hard landing” of slowed growth’, rather than an equitable transition.

What if we looked in different ways at places like Japan? Beneath the statistical cloud cover, might there be alternate patterns of hope being carefully pieced together, helping us imagine what such a slow-growth bioregional society would actually look like, how it would work and what it would feel like?

Last December, I visited Kagoshima prefecture in the far south-west of Japan, for a short field trip culminating in the Circular Design Week conference organised by the Japanese design firm Re:public. Every day, we visited traces of alternative economies working within today’s economy, apparently emerging because of slowdown, not despite it.

In these small towns, the patterns of enterprise seemed more redolent of the biological processes of fermentation, as with the local koji, than the normative extractive language of start-up and scale-up. Indeed we started the tour by examining koji in a shōchū distillery, which may have been a cleverly orchestrated performative pun from Re:public, as the koji mould is also ‘the starter’ for miso, mirin, shōyu and more besides.

We moved on to Kagoshima City, where the owner of two successful kindergartens is now acquiring a vacant elementary school offered up by the municipality, filling the latter with the kids from the former. Risa-san works with local farmers who provide school food – which is also food for education, as the kids learn how to make miso, how to ferment and also how their food waste goes back to the farmers as compost in tight circular loops – as well as running a farmers’ market and café (EAT LOCAL KAGOSHIMA). She tells me 50 per cent of the food’s ingredients comes from around the city, and the other 50 per cent from the wider prefecture. This is vertical integration (of schools) and horizontal integration (of food systems), and yet with no misplaced ambition to turn into McDonalds. This works because it stays local, based on bioregional material flows yet woven from personal relationships supporting culture, learning, food and agriculture.

In Hioki, a former Deloitte consultant from Tokyo has found a new life helping rebuild the local fishing industry, exploring how to cultivate the traditionally-farmed delicacy of moon scallops yet working within sea waters whose rising temperatures and decades of overfishing have denuded ecosystems, and with an ageing industrial workforce. Elsewhere in Hioki, a local entrepreneur is locating and re-opening vacant houses, or ‘akiya’, and connecting to super-local networks of energy microgrids and electric buses. He’s moved his business into the town, constructing a new headquarters in timber, adjacent to a small community centre largely made of cork, which is made available to locals for free. Elsewhere again, a closed factory creates space for an olive farm, with oil and cosmetics business, the first in Kagoshima region. We visit the tireless advocates for circularity in Osaki Town, the municipality with the highest domestic recycling rate in Japan. Re:public have themselves created a pop-up bamboo construction workshop and fab lab – ‘Re:Store’ – in a vacant storefront in downtown Satsumasendai, the accessible touchpoint of a broader ambition to reboot the maintenance of neglected forests surrounding the town.

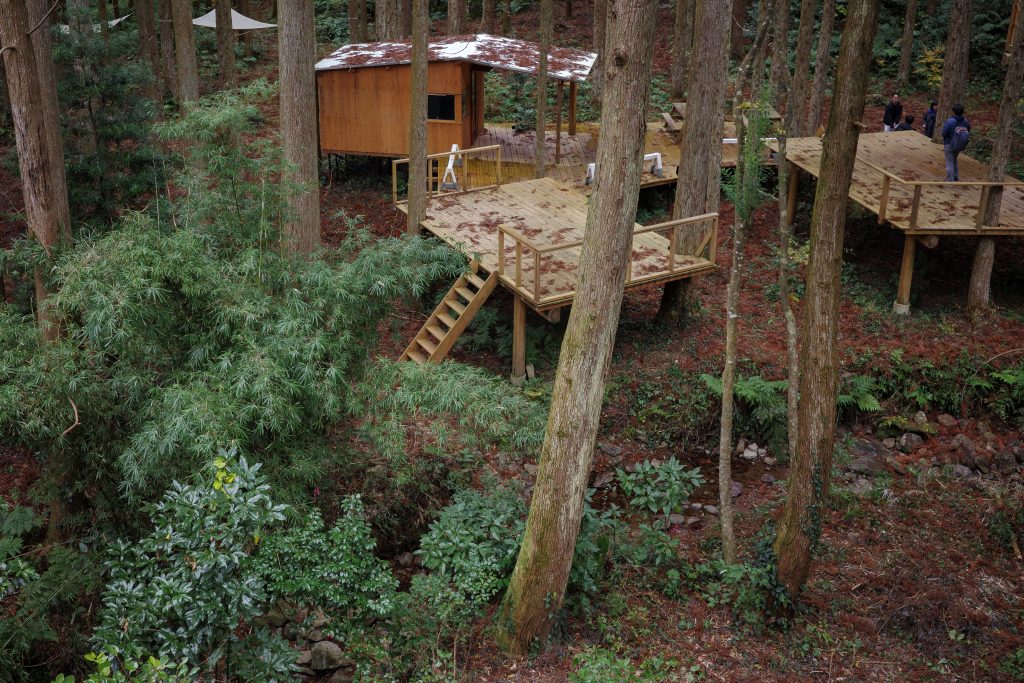

Deep in the woods near Minamikyushu, another abandoned elementary school is transformed into a thriving community arts centre, Kawanabe, activated by a hugely popular music festival running on-site – Good Neighbors Jamboree – and flanked by a network of Endor-like buildings and walkways newly threaded through the forest, constructed by and with local people and local trees. Everything here is impeccably realised and maintained, yet also relaxed by the vernacular loose-fit assemblages typical of Japanese everyday spaces. According to Kawanabe’s Shuichiro-san, when retrofitting the old school building, its older wooden components, built with local wood and maintained accordingly, had remained in excellent condition. The problems lay in the cheaper, newer replacements, like UPVC window frames from who knows where, broken and irreparable. They were replaced with timber from the forest outside the window.

All of these examples reverse the externality-ridden ‘economic miracle’ dynamics of late-20th century Japan: they scale down not up, refining in place and growing slowly, with care, and they create local loops at bioregional scale, based on the richness of local materiality and culture.

Equally, to some extent all of these ‘weak signals’ are only possible due to the financial value placed on the land and property tending to zero, which Saito would perhaps describe as property’s exchange value diminishing in favour of its intrinsic use value. Only once a century-old elementary school becomes worth almost nothing in property market terms can it be reimagined, re-built and re-valued by the community as an arts centre. A beautiful old building sitting within a beautiful old forest can conjure new value thanks to the inventiveness and perseverance of locals. The value is of a completely different kind to that valorised in the last century, precisely because the population will never significantly increase again.

Rather than seeing these vacant schools, shops and ‘akiya’ as half-empty, perhaps we see them as half full? Half-full of memories, of culture, of networks based on the propinquity of existing infrastructures. Half-full of materials, and thus embodied carbon, and of nature. Japanese urban planners speak of the ‘spongification’ of cities created by these akiya. 4 Shin AIba, in Yuma Shinohara and Andreas Ruby. Make Do With Now: New Directions in Japanese Architecture. Christoph Merian Verlag, 2022. Yet each of these holes is a possibility; an incomplete city is one that can adapt.

What strikes me about the people we meet in Kagoshima are these patterns of slowness, patience, resourcefulness, ‘staying with’ complex local systems, building health and pleasure – an even reciprocity between nature and culture.

This is not degrowth. Instead, amid the koji and kindergartens, we see another dynamic. Perhaps growth as in a forest, rather than a Tesla or an Exxon. A forest grows without destroying everything around it. But it still grows. This is an organic growth, a slow growth, and as Suzanne Simard has shown, the forest is a far more complex and ambitious idea than anything modernity has yet realised. 5 Suzanne Simard. Finding the Mother Tree. Allen Lane, 2021 The growth is more akin to the fermentation, of culture and cultures, that sits underneath those Kagoshima stories.

This version of Kagoshima doesn’t feel planned. These are simply moments, experiences, possibilities. The official plan for Japan relies partly on those national ‘moonshots’, high-tech plays which perpetuate existing modes and models, and whose very name harks back to a Mad Man mid-century modern. Kagoshima’s ‘moments’ described above are essentially the opposite; they are equally inventive, yet are also humble, careful and grounded, feeling for the edges of possible futures outside of the official narrative.

These moonshots and moments are unconsciously countering each other, a combination reminiscent of Karl Polanyi’s ‘double movement’. 6 Karl Polanyi. The Great Transformation. Farrar & Rinehart, 1944 Yet as Saito suggests, without actively reframing our ideas of economy and politics these two opposing engines will begin to shear each other apart. Polanyi, were he around, might suggest incremental experiments to more carefully and consciously guide these double movements. This would include slowly recalibrating national and regional governance, salvaging what works in the state, while ensuring these local commons-oriented shoots can take root and flourish. In this more complex view, we recognise, as Saito does, that the ‘moments’ above must still rely upon the Japanese state, in terms of universal healthcare, good infrastructure and social supports, just as they currently also lean on Apple and Sony. The theory of change as to how we might braid this patterning, rather than simply observing the shearing apart, is largely missing in Saito’s book. Again, his certainty of outcome leaves little room for the necessary ambiguity and openness we will need to address complexity, while there is little definition of the qualities and capabilities with which to do so.

So which practices must be brought to bear, to complement the humanities while keeping the sciences in check, and how? Dougald Hine writes in At Work in the Ruins, that art’s job is not to clear up confusion or communicate precise instructions, but ‘to complicate matters’. 7 Dougald Hine. At Work in the Ruins. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2023 Design’s job is to work similarly with ambiguity, but also to draw freely from science, engineering, arts and humanities in order to articulate possible futures; to capture the essence of ideas like Saito’s slowdown and bring them closer to form, to things, into experiences, situations, structures and settings in which to encounter these ideas.

In doing so, would this help with our question of what would a truly bioregional commons feel like? Saito’s book gives us structured analysis and the broad sweep of intellectual history that beguilingly sets up such questions. But we are left with careless gaps in language – ‘degrowth communism’ is unlikely to take wing as a phrase any time soon, whereas ‘slow growth’ or ‘commons’ could do – as well as a lack of scaffolding with which to build alternative imaginings of everyday life. We need to move beyond prose and explore practice. Well-researched and embedded speculative and strategic design, prototyping in and with places, might well ‘complicate matters’, but usefully so. It may figure out a theory of change through practice, thinking through making. Perhaps one answer, at least to the question of what bioregioning might be, can be found hiding in plain sight, amid the forests, fab labs and farms of Kagoshima.

I can’t say whether my observations of Kagoshima are the weak signals of a broad future, or the distracting motes of a false dawn, a brief hiatus from the ‘hard landing’ of inexorable decline. Yet I do think that it is in places like this that we might see something emerging, if we find new ways of seeing, of engaging. This is not the grand plan of ‘radical degrowth communism’. It is somehow more mundane, more everyday. Yet there’s a quietly complex, determined beauty to these unfolding relationships, a composting of value and a compositing of ideas, immersed in a specific sense of place drawn from both deep past and near future. It somehow feels like a more plausible future. Yes, based on forms of bioregioning, local commons and slow growth, but also globally-connected, vivid, alive, half-full of diverse possibility. It is up to us to begin embedding and immersing ourselves in these worlds as they are forming, by recognising the possibility of another double movement – not as if a grand plan but the glimpses of uncharted paths leading through the forest ahead.