Alive to Place

The catalogue for a show about architect Anupama Kundoo frames her work through the concept of abundance. This emphasis on craftsmanship and local materials is one that is finding resonance all over the globe

Abundance Not Capital is the intriguing title of a solo exhibition of the work of architect Anupama Kundoo at Vienna’s Architekturzentrum this autumn. 1 Abundance Not Capital: Anupama Kundoo runs until 9 March 2026. Source The show and its accompanying catalogue signal a welcome continuation of Kundoo’s growing profile in Europe, and across the project, curators and editors Angelika Fitz and Elke Krasny make a case for the ‘lively architecture’ of their subject as an exemplar of abundance in various forms. As well as allowing a moment to celebrate Kundoo’s work, the show and catalogue prompt the question of how we might understand ‘abundance’ as a conceptual framework in architecture, and whether it deserves greater consideration as the discipline grapples with the frictions between building and the climate crisis.

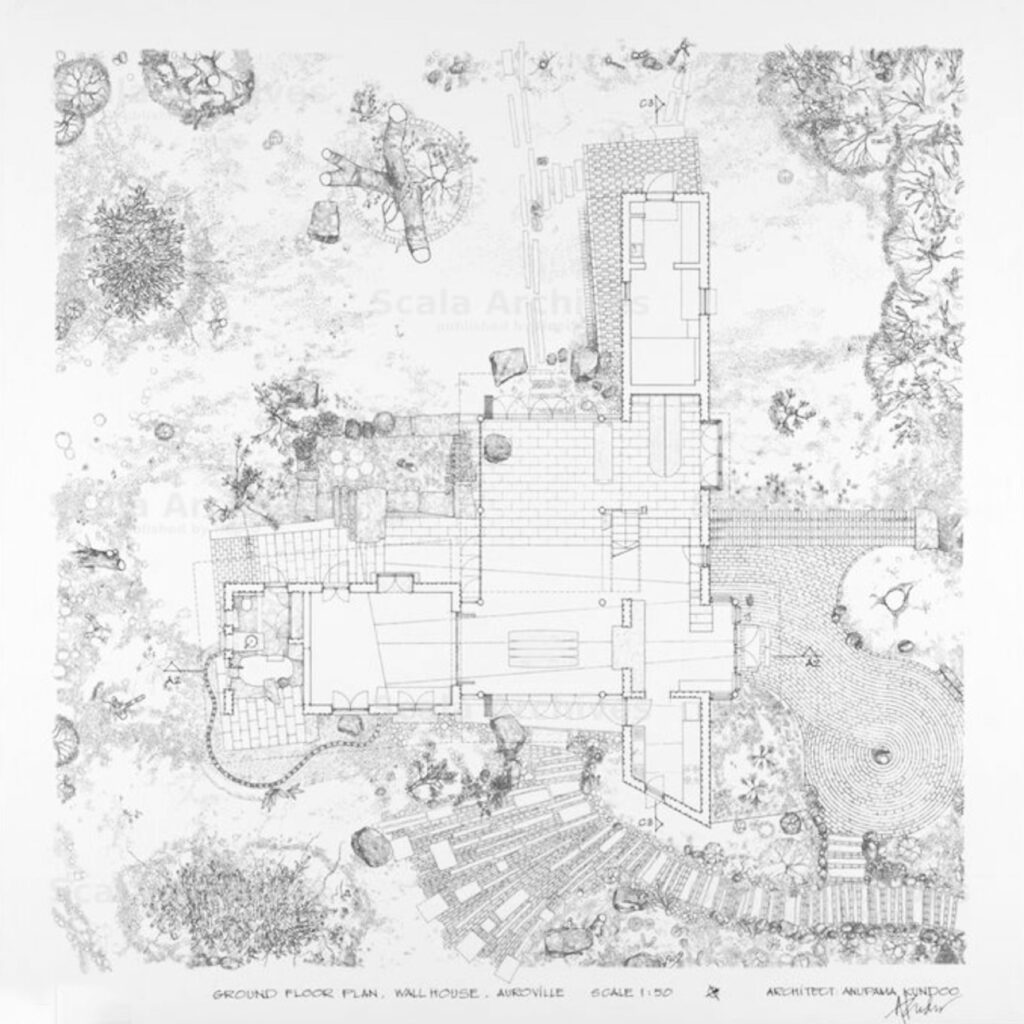

Anupama Kundoo first arrived on the European architecture scene in 2012 at the Venice Biennale where she presented a 1:1 scale model of her 2000 project, the Wall House. Described by David Chipperfield at the time as a ‘lyrical modernism’, the display was constructed by Kundoo, alongside a team of Venetian students and Indian craftsmen, in the space of the Arsenale. The overt presence of this skilled workmanship, which featured brick walls and terracotta ceiling elements, stood in contrast to the rather uniform neo-modernism that dominated the exhibition. The installation was indicative of an approach to architecture that is now being embraced by a younger generation.

Born in Pune, Western India in 1967, Kundoo studied architecture in Mumbai in the mid-1980s and set up her eponymous practice in 1990. The subsequent decades have seen the completion of a dozen or so projects in Puducherry, a large city on India’s east coast, and in neighbouring Auroville, an experimental international community of around 3,000 people designed by French architect Roger Anger. The projects are largely civic and social – halls, community centres, co-housing and a daycare facility – as well as some more maverick homes such as the Wall House, where Kundoo still lives, and the Volontariat Homes for Homeless Children (2008). With their highly sensitive approach to context and combination of low-tech methods with sophisticated materials – the Volontariat Homes are clay mounds, each ‘fired’ like kilns, an ingeniously cheap way of producing structurally sound dwellings – projects such as these have caught the attention of curators and institutions in Western Europe. Kundoo’s installation in Venice in 2012, along with her participation in group exhibitions such as Critical Care at Berlin’s Deutsches Architekturzentrum and a solo show at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, both in 2020, have established her reputation outside of eastern India. 2 The exhibition Critical Care. Architecture for a Broken Planet, co-curated by Fitz and Krasny who also edited the publication, was first presented at the Architekturzentrum in 2019 and subsequently travelled to other venues including the Deutsche Architekturzentrum in Berlin .

At the Architekturzentrum, the catalogue’s focus on abundance is a pointed departure from a chronological or project-led monograph. The publication explores Kundoo’s work thematically, each chapter centring around a different ‘Abundance’ in her work: an abundance of knowledge, abundance of materials, abundance of solutions, aspirations, differences, generosity, nature and regeneration. We can surmise from the project’s title that ‘Abundance’ is meant to be understood in opposition to ‘Capital’, but because the term itself is never properly defined by the editors, an understanding of Kundoo’s architecture as a departure from conventional practice remains unclear. Similarly, the liberal application – the very abundance – of the word ‘abundance’ throughout the catalogue transforms it into something unspecific. As a result, it loses its potency to describe ‘architecture otherwise’. Or, to put it another way, with the seemingly boundless application of the concept assigned by the editors, it’s difficult to see why ‘abundance’ in this context isn’t also used to describe extractive ways of building – an abundance of profit, say, or an abundance of embodied carbon or an abundance of exploitation.

And yet, a number of ways the catalogue frames abundance are particularly useful for understanding Kundoo’s output, not least in how it resonates beyond her specific context. The first two chapters explore the ‘Abundance of Knowledge’ and the ‘Abundance of Materials’, cutting to the core of the architect’s ingenuity and originality. Wall House (2000), which features prominently in the opening chapter, is a key case study in her oeuvre and the kind of ‘built manifesto’ that is usually located at the start of a young architect’s career. As a free-flowing two-storey 220m2 structure, built in Auroville for Kundoo herself, Wall House is as much a home as it is a testing ground for construction techniques. To realise the project, the architect drew from and developed techniques and skills local to the area, experimenting with terracotta forms and traditional clay pots to give shape and volume to ceilings. In the house, which combines four different roofing systems, locally made cone-shaped terracotta elements are joined together to create textured vaults that keep the building cool by allowing air to circulate. The same method was later used by Kundoo for social housing and holiday home projects in 2003 and 2016 respectively. In the chapter titled ‘Abundance of Materials’, the editors highlight Kundoo’s use not only of terracotta but also of stone, earth and recycled wood. ‘It’s not about building materials that are certified as “good” or “bad”,’ they write, ‘but rather about maximizing what lies around in abundance through creativity, working relationships, and local cycles.’ Granite, for example, is richly available in the region around Auroville and so was used in Kundoo’s first home, the Hut Petite Ferme (1990), as well as the Wall House. As Fitz and Krasny explain, Kundoo works closely with stonemasons to identify stone that requires minimal processing, thus reducing the environmental cost and allowing the material to retain its natural character.

With these chapters in mind, we might consider abundance in Kundoo’s work as the ‘innovative use of materials and techniques that are locally available’ – that is, an approach to architecture whereby the design and final form of a building is shaped by what is already available, not that which is imported. There is, perhaps, an inevitable comparison to be made here with the idea of the ‘vernacular’ – a term which has taken on new hues in design discourse in the context of the climate emergency, even if Kundoo herself has rejected it. As Shumi Bose argues elsewhere in the catalogue, if the architect, ‘as somebody trained in the Global South, would invariably elicit the use of this word “vernacular,”’ the concept ‘seemed rather a gross simplification’ when applied to Kundoo, who is ‘adamant in defining hers as a modernist approach’.

If vernacular, then, refers to a sort of pre-modern, craft-like approach to making, then abundance seems to capture both the contextual specificity of Kundoo’s work and, crucially, a critical response to mainstream architecture and construction in West India and beyond. For Fitz and Krasny, as well as in Kundoo’s own writing, an ‘abundant’ practice stands in contrast to the use of ‘expensive materials’, ‘perfected industrial products’ and standardisation, all of which are among the key components of dominant construction practices. Writing in The Plan Journal in 2021, Kundoo asks ‘How can we expand human potential so that our economic assumption shifts from scarcity to abundance?’ She characterises the professions of the built environment as operating with a misguided sense of scarce time, where efficiency is prioritised over all else at the expense of natural resources and quality of life. ‘The idea’, she writes, ‘is to imaginatively and purposefully use our time to create an abundance that can benefit all’, meaning a reduction in the environmental footprint of a building, housing for more people, teaching building trades and skills and supporting local economies.

For all the specificity of her practice, there are clear resonances between Kundoo’s work and that of others in different contexts. One might think of Material Cultures in the UK, Francis Kéré’s work in Burkina Faso, MASS Design Group’s work in Rwanda or even Rotor’s work in Belgium. Each of these architects uses research and local material resources – be those in the ground or in underused buildings – to establish new frameworks for practice. For example, Kéré’s Atelier Gando in central Burkina Faso is both a construction site and laboratory for material testing, while the Adobe Block Standards developed by MASS provide formal guidelines for safe adobe construction in Rwanda. These are replicable ways of working which lead not only to new buildings but to new systems from which buildings can emerge. Abundance thus acts as a thread to tie these different practitioners together: a way of describing a group of ecological and socially sensitive designers with a shared approach that forms a contrast to orthodox extractive construction.

In Kundoo’s own work, this approach is exemplified in her architectural drawings, one of the few aspects of her practice where sole authorship is discernible and perhaps where an architecture of abundance is most legibly distilled. The plan and section drawings of the Wall House are made with rectilinear precision and close attention to material detail. But, tellingly, the building itself competes for attention with the trees, grass, rocks and other elements of the landscape, which are rendered with such intricacy that they surround, overlook and even embrace the brick structure. In these drawings, the Wall House appears at home on the same ground from which the plant life emerges. The drawings describe an architecture that must not dominate the natural world but should instead exist alongside and perhaps in deference to it – an architecture alive to place and connected to an abundant planet.