Islands of Coherence

Zooming out from the practice of bioregional design, what systemic shifts would be required to unlock its radical potential? We explored that question with a roundtable of experts, and our conversation is distilled into this strategic overview

Bioregioning offers an alternative organising principle that could redefine the way we understand material flows, political governance and civil society. Simply defined, it is a form of activity that operates within the natural boundaries of a bioregion – often defined by a watershed or geological area – and that seeks to sustain, or indeed revive, the health of local ecosystems. It uses the bioregion as a form of template for organising and making. While bioregions are landscapes, bioregioning is an attitude or an approach that is less about redefining borders – what is in and what is out – than it is about re-establishing our connections to the local landscape and its cycles. More than that, it is about building the network of local knowledge that would mean critical decisions are made in the best interests of the bioregion, and, crucially, that local citizens have greater agency in those decisions.

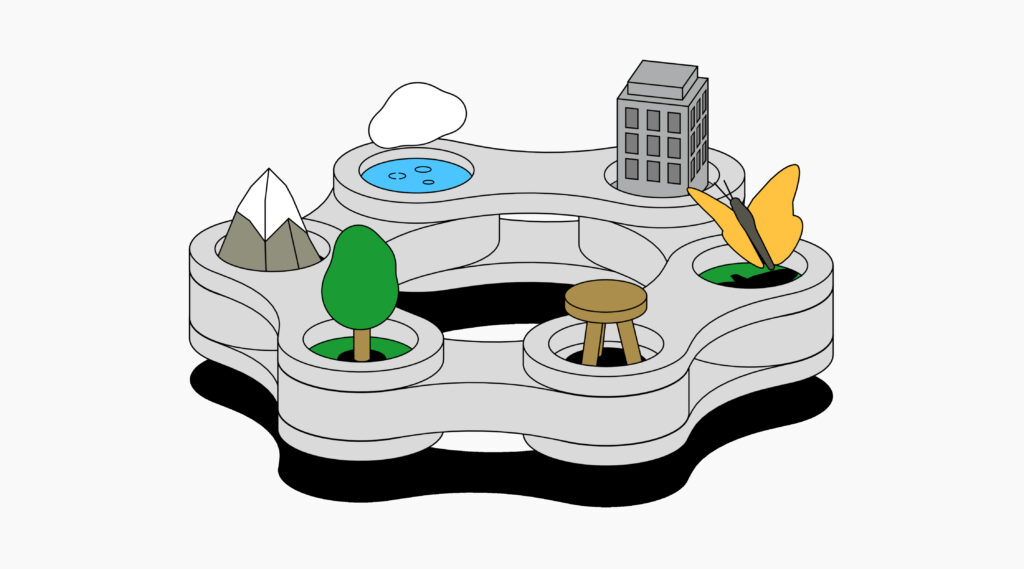

The overlapping layers of natural boundaries and political jurisdictions are complex, often incoherent, and certainly not mutually supportive. The opportunity of bioregional thinking is to create what Ilya Prigogine called ‘islands of coherence’ amid a ‘sea of chaos’. 1 The full quote reads: ‘When a complex system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to shift the entire system to a higher order.’ However, while the quote is widely used on the internet, the source is mysterious. It is sometimes wrongly attributed to I. Prigogine and I. Stengers, Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature, Bantam Books, 1984. If you know the source, please do get in touch. Coherence emerges when the activities of a landscape, its people, its local knowledges and its politics overlap to the benefit of all. That is especially true in a world where climate resilience will often be best understood and delivered by local citizens rather than central governments.

Throughout this issue we have encountered bioregioning as a form of design practice, but what are the implications of this work at a more strategic level? What are the obstacles to bioregioning becoming a more mainstream way of thinking and working? What engrained systems and patterns of thought would have to change? What political or economic structures would need adjusting? And, finally, what policy measures could support bioregional organising and citizen participation?

As we explore those strategic questions, it may be useful to keep two bioregional case studies at the back of our mind. The first is a deep and detailed exercise in building with bioregional materials conducted by Atelier LUMA in Arles. The second is an extensive network of local knowledge and civil society partners established by the Bioregional Learning Centre (BLC) in Devon. Each in its own way surfaces the enormous opportunities and challenges of creating bioregional islands of coherence.

Case study 1: Atelier LUMA

Atelier LUMA is the design research lab of the new art centre LUMA Arles. It was established to explore the potential of bioregional materials and production methods, and it used its own buildings as a test site. Through a series of residencies, designers are testing the potential of agricultural waste streams and other biomaterials from across the Camargue to produce building components and finishes – many of them drawn from industries for which the region is famous, such as rice, salt and sunflowers. Atelier LUMA worked with the Belgian practice BC Architects and the British architecture collective Assemble to restore a series of warehouses using timber and rammed earth. Through design residencies, the biomaterial research was prototyped into a whole range of unconventional natural finishes. These included salt-crystal panels used to line the elevator shaft of the Frank Gehry-designed art centre, insulation panels made from waste sunflower stalk, rice-straw acoustic panels, mosquito gauze made from Japanese knotweed, wall tiles 3D printed from algae filament, upholstery produced from low-grade wool and a range of local yarns and textiles dyed with plant-based pigments produced in LUMA’s own dye lab. Since its inception in 2017, Atelier LUMA has represented the most significant effort to test bioregional design and manufacturing methods in Europe, and remains a vital system demonstrator with the potential to expand into a global network of bioregioning hubs sharing and exchanging knowledge with other distinct regions.

Case study 2: The Bioregional Learning Centre

The Bioregional Learning Centre is based in the UK’s south Devon bioregion and was established to build the network of collaborations required to shift the area to long-term climate resilience. Like Atelier LUMA, it was founded in 2017, and was inspired by Donella Meadows’ idea (which you can find published in this issue) that this kind of distributed work requires a centre. The BLC seeks to make the connections between local government, the private sector and citizens themselves to address issues such as biodiversity loss, flood management or the consolidation of regional knowledge. Central to its mission is the foregrounding of civil society, based on the belief that the people invested in a place are best placed to make the right decisions to steward its future. The BLC gives citizens the agency to co-create the story of the bioregion, or to understand ‘who’ the place is. That means revealing the underlying systems, identifying where to take action and how to connect the varied bodies required to achieve a particular impact. The BLC sees itself as the connective tissue between silos, as well as a process of ‘action learning’ that allows people to learn together how to address the challenges facing south Devon.

—

These two case studies help make tangible the opportunities and limitations of bioregional design. They also raise a number of useful questions about governance and citizen participation. When it comes to building, making or producing, any bioregional project inevitably runs up against questions of scale, so that seems a fitting place to start.

Scaling up versus scaling out

Every bioregion is unique. And no bioregion can produce all the materials its inhabitants need to sustain a modern way of life. Every bioregion will be suited to some materials and certain kinds of product, and not others. Atelier LUMA thinks in terms of a model that we are more likely to associate with wine: the terroir. A terroir is defined by the soil, the climate and the people of a particular place. The Camargue is best suited to materials made from salt, sunflowers and algae. It is not well suited – perhaps no bioregion is – to the manufacture of digital technology, which would demand a palette of metals, minerals and plastics drawn from diverse global supply chains. So, what kinds of materials are best suited to bioregional production? In Atelier LUMA’s case, it was construction materials. That is not just for practical reasons but also because of potential impact. Construction and the built environment account for 37 per cent of global emissions, including both the embodied carbon of the materials themselves and the energy buildings consume when in use. And so, construction materials are where the greatest gains of bioregional design are to be found.

Any architect setting out to build bioregionally will soon run aground in the realities of construction supply chains. Trying to use local materials, let alone new or untested ones, will have contractors, planners and insurers giving you short shrift. It takes a huge amount of labour – bureaucratic, manual and emotional – to work outside of standardised supply chains and regulatory norms. And so, as one architect put it, they find themselves ‘talking bioregionally but acting globally’ because of the supply chains. Accepting that Atelier LUMA is very much the exception, it nevertheless establishes some key principles both for how to build and how to rethink the growth model.

The links that Atelier LUMA has forged with local agriculture have yielded new materials, new production processes and thus new business opportunities. But the standard economic model of seeking continual growth in these new supply chains cannot apply. The bioregion will have its natural carrying capacity. Seeking greater production through optimisation and efficiency would require monoculture models that we know result in over-extraction, soil depletion and loss of biodiversity. So there are natural limits to what the terroir can produce, and these demand an alternative approach to the conventional demand to ‘scale up’.

Atelier LUMA’s mantra is: ‘Materials are heavy and should stay local. Ideas and people are light and are global.’ This deceptively simple axiom – materials are heavy, ideas are light – suggests that scale is achieved not by exporting materials from the Camargue to Spain or Italy but by exporting the principles of bioregional design instead. How can similar materials be sourced from local terroirs? Can the recipes be adapted with local ingredients? For instance, in a collaborative project in Korea, Atelier LUMA explored recreating their algae wall panels with a local Korean species of algae.

One of the drawbacks of the ‘circular economy’ is that it mainly applies to a few dominant industrial materials, and even then only a small percentage is ever recycled. The key to local production is to diversify the material palette, drawing on local landscapes and waste streams. Each material is a new set of relationships. The success of a bioregional production system should be measured by the number of connections in the network. Then one can measure the quality of those connections – are they thick or thin? And that applies globally, or let’s say multi-regionally. Rather than exporting materials (the growth model), you are exporting ideas (the proliferation model). Atelier LUMA hopes to establish an international network of bioproduction centres where material experiments, recipes and principles are exchanged. We need a new definition of scale that is not about the production volumes of a material but the proliferation and exchange of knowledge. From scaling up to scaling out – or perhaps from scaling up to skilling up.

Who’s funding the transition?

How feasible is bioregional design and production? It is worth saying that Atelier LUMA is privately funded by the LUMA Foundation, and are under no illusions that they currently represent a viable, profitable business model. Bioregional experiments such as these currently take place in the sheltered contexts of projects funded by non-profits or in community-led initiatives where inefficiencies are compensated for by the drive and surplus energy of the participants. In the UK, there are precious few housebuilders willing to eat into their profits or timelines to experiment with bioregional materials. And that’s within the private sector. If one was to entertain this approach in the state-funded sector, say for the construction of a school, one would soon fall foul of stringent national standards and regulations.

While the UK government has set itself a target of being net-zero by 2050, it has put almost no policies in place to reduce the embodied carbon of the construction sector. And while policy-makers are certainly aware of the carbon burden of construction, bioregioning is not yet a framework within which they approach the issue. What is required to put bioregioning on the policy agenda is a system demonstrator of sufficient scale to act as a proof of concept. If the government were to invest in a pilot project it would offer a valuable test case of how bioregioning might be one strategy in its net-zero arsenal. In the meantime, there is a role for cultural institutions and civil society to advocate for such approaches.

What does bioregional governance look like?

We’ve already established that bioregioning, by definition, cuts across established local authority boundaries and jurisdictions. So how is it to gain any purchase at the local authority level, let alone at a governmental level? Government sets national targets for housing, carbon emissions or growth and then deals them out across the administrative regions. ‘Bioregion’ is a not a term that a policymaker will recognise from their day job.

However, one structure that is emerging is the Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS). LNRSs, as defined in the Environment Act 2022, are ‘a new, England-wide system of spatial strategies that will establish priorities and map proposals for specific actions to drive nature’s recovery and provide wider environmental benefits’. Essentially, they are a regional strategy for addressing biodiversity loss and nature recovery by directing public funds to ‘nature-based solutions’. The West of England LNRS is currently engaged in a process of surveying local residents and gathering evidence from farmers and landholders with a view to gathering data and establishing priorities. Local knowledge, embodied in the region’s inhabitants, is an essential element of the process.

Data gathering and citizen participation

One of the crucial elements of bioregioning is data gathering and sharing. What kind of data? It might relate to biodiversity loss, water quality, ecological rhythms, the impact of flooding, the links between nature and mental health or waste streams that could be resources for local businesses. Often the data maps are very poor, perhaps extrapolated from national data sets and based on a per capita version for the region. The deep knowledge about a place is most likely held by farmers and engaged locals. But it is not likely to be in a form demanded by policymakers to substantiate calls for spending. It’s not just about quantifying, it’s about qualitative data of the kind that amounts to a form of collective intelligence.

In south Devon, the Bioregional Learning Centre has been convening a citizen observatory. The aim is not just to collect data but to interpret it and connect it to the right places. Here citizens act as interpreters, mediators and story-tellers. Part of the role is to humanise the data but also to facilitate collaborations by building a network across the bioregion. This peer-to-peer process often elicits more enthusiasm from participants than dealing with bureaucratic or stretched local authorities. Citizen participation is rewarding and empowering but it is also demanding. Building relationships and qualitative understanding are time and resource intensive. It’s work that people do in their spare time and of their own volition. How does a community sustain people’s engagement after the initial burst of enthusiasm and avoid processes fizzling out through exhaustion? To make these processes sustainable, should citizens not be remunerated for their time? As part of the development of its Carbon Plan to achieve net zero, the Devon Climate Emergency partnership brought together 30 organisations, and 70 people representative of Devon were paid to attend a citizens’ assembly, recruited by sending out 14,000 letters. But while the council was able to fund that as a one-off process, it is difficult to justify longer term on shrinking local authority budgets.

How can national policy facilitate bioregional thinking?

As James C. Scott explains in Seeing Like a State, government is an attempt to impose rational order on messy systems, but the results are sometimes absurd. One only needs to look at a map of London’s watershed lines to understand that one council’s flooding might emanate from the territory of another council without the incentive to fix it. We established early on that bioregioning cuts across jurisdictional boundaries, but it will also straddle the concerns of multiple government departments. Even within local government, issues will fall into the domains of siloed departments. In reality, however, a bioregional housing project might span departments for housing, planning, farming, food and skills. To be effective, bioregioning must be a systems approach for cross-silo and cross-boundary collaboration.

One of the potential outputs of local authorities engaging with citizen assemblies is the co-production of public policies. To date, citizen assemblies have rarely informed central government policy, but at the local level, as we saw in Devon, the will is there. Greater devolution to local authorities would mean more flexibility to set appropriate local policies and budgets. Indeed, it might allow local authorities that share a bioregion to co-fund initiatives that cross each other’s borders. Again, pilot projects such as bioregional design and manufacturing workshops are useful system demonstrators to test and focus those such collaborations. Bioproduction labs are fertile ground for unlearning the old paradigm of industrial modernity that held that we are separate from nature, helping to rebuild our connection to landscapes and ecosystems.

Finally, one must acknowledge that some of the practices outlined above will involve a shift away from established ways of doing things, from patterns of behaviour that may stretch back generations. It might involve transitioning the use of a field from one crop to another, the rewilding of a once profitable plot or the abandoning of a road that is increasingly subject to flooding. Community initiatives and policymakers alike must recognise that such issues will have an emotional impact, and nurture a flexible culture that helps people deal with change. This is especially true in a context where local MPs, in their effort to appeal to their constituents’ desires or to keep established livelihoods and behaviours alive, might find themselves fighting against change. Bioregioning and climate resilience will often require an acknowledgement that, in fact, things can’t be ‘the way they’ve always been’. How can citizen-led initiatives and local authorities take people on that journey?