On Being Inside Gaia

In the 1970s, British scientist James Lovelock developed a unifying theory of the planet as a coherent, living entity: the Gaia concept. Tracing the evolution of the theory in the subsequent decades, artist and writer James Bridle expounds more-than-human design as a way of both co-constructing the world and reconstructing ourselves

When I try to picture a more-than-human design object, the first thing that comes to mind is a pair of padukas, a traditional form of footwear in South and Southeast Asia. Paduka come in many forms, but most commonly as wooden soles, with a knob positioned between the big and second toes. They may be elaborate, as those padukas which form part of a bride’s trousseau, or those which are venerated as holy relics, or they may be extremely simple. What many have in common is two narrow, curved stilts, which reduce the wearer’s footprint and elevate them above the ground in order to ensure that the principle of non-violence, practiced by the saintly followers of the Hindu and Jain religions, is not violated by the accidental trampling of insects and vegetation. 1 ‘The Paduka’, Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, Canada.[Source]

Some followers of specific sects, particularly among the Jains, might go further: carrying a broom to sweep the ground in front of them as they walk, or wearing mesh masks to avoid inhaling insects accidentally, but the use of the paduka is widespread. 2 Ron Cherry and Hardev Sandhu, ‘Insects in the Religions of India’, American Entomologist 59, 2013, 200–202. All of these practices speak to an attentiveness to the world of other beings, the more-than-human world, which surrounds and holds us at all times. In the words of a Brahmin prayer: ‘Forgive me, Mother Earth, the sin of injury, the violence I do, by placing my feet upon you this morning.’ 3 Uday Dokras, ‘Ancient Footwear of Bharata’, The Journal of Indo Nordic Author’s Collective, 2020.

The paduka is perhaps not quite right, not exactly what I mean when I try to imagine a truly more-than-human design, as we shall see, but a prayer is a good place to start.

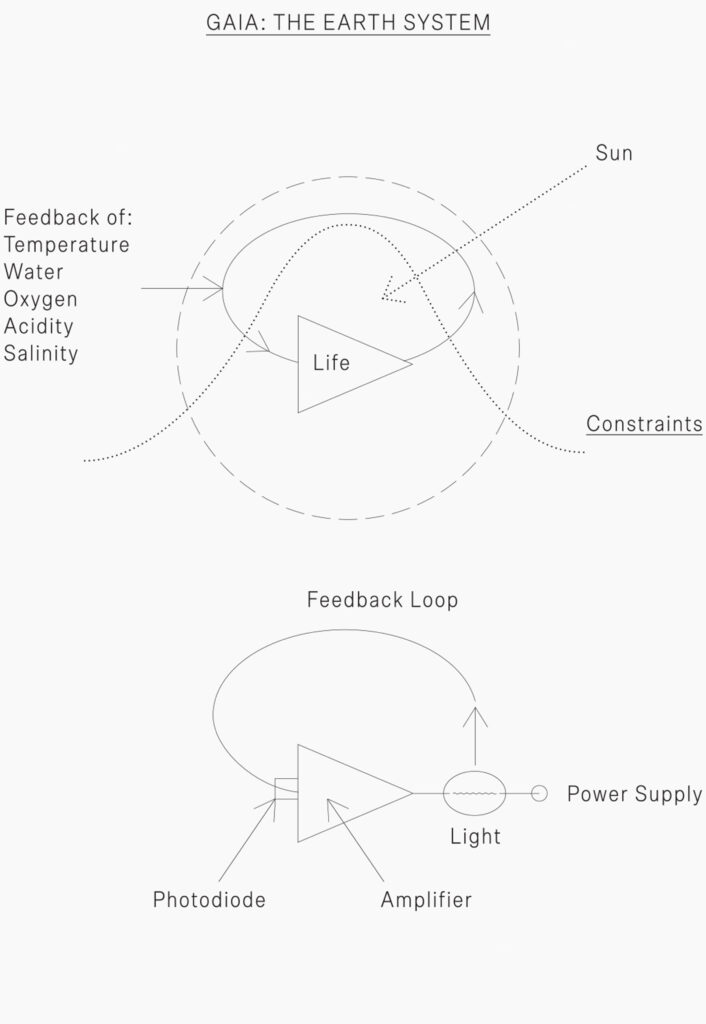

In the 1970s, James Lovelock, a British scientist then working for NASA, proposed a novel way of understanding the whole Earth system, which he called Gaia. In its original formulation, Gaia was a wholly scientific proposition, emerging from systems theory and atmospheric chemistry: ‘a biological cybernetic system able to homeostat the planet for an optimum physical and chemical state appropriate to its current biosphere.’ 4 James Lovelock, ‘Gaia as seen through the atmosphere’, Atmospheric Environment 6, 1972, 579–80. Within a few years, however, the Gaia concept metastasized into something much more vibrant and vigorous, a cultural figure who crossed over from scientific into popular discourse.

There are two generally agreed reasons for this. The first is the magnetism of the figure itself – or herself. Given the name of the ancient Greek goddess of the Earth (by Lovelock’s then neighbour, the English novelist William Golding 5 James Lovelock, The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth. New York: Norton, 1988. ), Gaia appealed to a growing popular ecological consciousness. For the first time, there was a unifying vision of the planet as a coherent, living entity. This vision was further brought into fruitfulness by Lovelock’s association with the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, who collaborated with Lovelock on a series of books and journals. 6 See, for example, Margulis L and Lovelock J, ‘The atmosphere as circulatory system of the biosphere: The Gaia hypothesis’, CoEvolution Quarterly 5 (Summer), 1975, 31–40. This collaboration produced ‘a fully geobiological Gaia concept’ which not only enfolded Margulis’s symbiotic concept of the origins of life into Lovelock’s homeostatic planetary system, but positioned it as an ‘attitudinal, paradigmatic’ change in scientific understanding of life on Earth, and the Earth itself, as fundamentally inseparable. 7 Bruce Clarke, ‘Rethinking Gaia: Stengers, Latour, Margulis’, Theory, Culture & Society 34.4, 2017, 3–26.

In the subsequent decades, while Lovelock and Margulis’s theory was hotly debated, and often derided, others took up and mobilised the figure of Gaia into something – or someone – even more active. The philosopher of science Bruno Latour, in his 2013 Gifford lectures delivered at Edinburgh University, figured Gaia as a ‘secular deity’, a ‘name proposed for all the intermingled and unpredictable consequences of the agents, each of which is pursuing its own interest’. Gaia is not ‘old nature’, nor does she ‘play either the role of inert object that could be appropriated or the role of higher arbiter’; rather, Gaia is a manifestation of the Earth itself overcoming the old separation between nature and culture that has guided humanity for millennia, and ‘an injunction to rematerialize our belonging to the world’. 8 Bruce Clarke, ‘Rethinking Gaia: Stengers, Latour, Margulis’, Theory, Culture & Society 34.4, 2017, 3–26. Such a materialisation is undoubtedly a concern for design.

The Belgian philosopher Isabelle Stengers takes this assertion further, naming Gaia ‘the Intruder’, a force which manifests the duress and resistance of the Earth system itself. ‘Gaia is ticklish,’ she writes, ‘we depend on her patience, let us beware her impatience.’ 9 Isabelle Stengers, Thinking with Whitehead: A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts, trans. Michael Chase. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011 [2002]. At the same time, Stengers (and Latour) are careful not to personalise Gaia, and resist a spiritual association with the Goddess: ‘To name is not to say what is true but to confer on what is named the power to make us feel and think in the mode that the name calls for.’ 10 Isabelle Stengers, In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism, trans. Andrew Goffey. Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press, 2015 [2009].

Meanwhile, Lovelock’s position, always cantankerous, turned darker. The titles of his books, in which he has explored the ramifications of Gaia theory and the exponentially accelerating effects of climatic change, reveal this shift in perspective: from Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (1979), to The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back – and How We Can Still Save Humanity (2006), and The Vanishing Face of Gaia: A Final Warning: Enjoy It While You Can (2009). By 2019’s Novacene, his last publication before his death in 2022, Lovelock was figuring Gaia not as the self-regulator and propagator of life, but as the vehicle of meaning which life creates. What was propagated by the system was intelligence, or information, rather than living matter. Thus, in his final vision, Lovelock imagined not a planetary flourishing, but the emergence of super-intelligent machines, evolving along Darwinian lines and powered by solar energy, which would carry Gaian generations out into the cosmos; in short, the Singularity. 11 ‘The Singularity’, an idea popularised by a number of Science Fiction writers as well as scientists and Silicon Valley moguls, predicts a coming age of superintelligent machines which will surpass all human intelligence, with either dire or wondrous effects on civilisation, depending on your viewpoint. It’s a depressing vision, understandably informed by a lifetime of railing against the ever-increasing degradation of the planet, but it leaves little hope for us, or the other beings we currently share the planet with. 12 James Lovelock, Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020.

There remains, however, a very different version of Gaia available to us, which resists both Lovelock’s doomerism, and the disenchantment of the scientist-philosophers. In an essay for The Ecologist in 1985, another philosopher, David Abram, seized upon Gaia’s origins in the atmosphere, in the very air we breathe and to which we contribute our own gases and emanations, to emphasise that we are a fundamental, living part of its operations; part of the vast circulation system which sustains all life. ‘If Gaia exists, then we are inside her.’ 13 David Abram, ‘The Perceptual Implications of Gaia’, Dharma Gaia: A Harvest of Essays in Buddhism and Ecology, edited by A. H. Badiner. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 1990. Originally published in The Ecologist 15, no. 3, 1985.

Abram had an unusual journey towards Gaia, and ecophilosophy. He spent the early 1980s traveling as an itinerant sleight-of-hand magician through Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, and eventually studying with Indigenous magical practitioners, including shamans, in Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Nepal. These magicians, he found, were also healers and often the primary carers in their communities, but they occupied a strange position: not fully accepted and, in fact, often actively distrusted by their neighbours. They tended to live on the edge of or at a distance from their communities, in communication with, and interceding on behalf of, the non-human community which surrounded them:

‘For the magician’s intelligence is not encompassed within the society; its place is at the edge of the community, mediating between the human community and the larger community of beings upon which the village depends for its nourishment and sustenance. This larger community includes, along with the humans, the multiple nonhuman entities that constitute the local landscape, from the diverse plants and the myriad animals—birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, insects—that inhabit or migrate through the region, to the particular winds and weather patterns that inform the local geography, as well as the various landforms—forests, rivers, caves, mountains—that lend their specific character to the surrounding earth.’ 14 David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Vintage, 1997, 14.

Spending time in and around these communities, Abram wrote in The Spell of the Sensuous, published in 1996, brought him closer not only to the other humans in them, but the non-humans which surrounded them. And this closeness was embodied: watching a heron fishing, he did not merely admire ‘its careful, high-stepping walk and the sudden dart of its beak into the water’, but felt ‘its tense yet poised alertness with my own muscles’. 15 Ibid., 24. When he returned to America, Abram felt this sense of closeness to the Earth and its inhabitants ebbing away. Torn from a cultural context which nourished it, this extended sense of consciousness became something it was necessary to actively cultivate, and, in doing so, he gave it a name: the ‘more-than-human’.

Over and above the division of human and non-human, of nature and culture, the more-than-human asserts that we are unique but not special. To be human is always to be part of an omnicentric, heterogeneous network of human and non-human others, where no being is ‘higher’ or ‘more advanced’ than any other. Embodied as we are, with our own set of senses and experiences, we cannot know what it is to be another being, and yet, embodied as we are, we share a world: we breathe, we bask in the sun, we drink cool water and we do other things, less easily explained, to one another, under the same sky. To invoke the more-than-human is to come into communion with Gaia from the inside, to recognise ourselves, and the things we make and do, as part of the infinite unfolding of life on Earth.

For all its growing environmental consciousness, design practice has struggled to fully realise this ecological vision, which directly contradicts the notion of the ‘environment’ as separate from ourselves and our creations. Furthermore, this division has been entrenched by the once-revolutionary promulgation of ‘human-centered’ design, which, from the outset, set itself explicitly against both the dehumanising effects of high technology, and the non-human world.

In one of the foundational texts of human-centered design, Architect or Bee?, in which the term ‘human-centered systems’ first appears, the engineer Mike Cooley argued that ‘we must always put people before machines’ but also that ‘if we continue to design systems [in a technology-first manner], we will be reducing ourselves to beelike behaviour.’ 16 Cooley takes the question from Marx, who, in complete opposition to Blake, considered the bee an exemplar of a lack of imagination. Architect or Bee? The Human Price of Technology. London: Hogarth Press, 1987, 7; 52. It’s painful, if revealing, that Cooley, one of the co-authors of The Lucas Plan, a radical programme for workers emancipation which espoused some environmental ideas, 17 David King and Breaking the Frame, ‘The Lucas Plan: how Greens and trade unionists can unite in common cause’, The Ecologist, November 2016.[Source] could not imagine an argument for elevating the rights and needs of humans without simultaneously degrading the beinghood of non-humans. Bees are, of course, far from mere drones: they form complex societies which engage in complex forms of communication and decision-making, which have been likened to the most progressive forms of participatory democracy. 18 See Thomas D. Seeley, Honeybee Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. We can, and must, do better than human exceptionalism, and human superiority. More-than-human design is an opportunity to do so, in its injunction for a mutual flourishing which respects the skills, intelligence and beinghood of all living beings.

We know now, from the work of Lynn Margulis, that we are all the products of symbiosis; her development of the theory of endosymbiosis showed that life emerged not from competition between distinct individuals, but as a result of the relationships between them. Symbiosis is not a vision of perfect harmony – far from it. The world is not composed of harmonious or even equitable relationships, but it is composed of relationships, and more of those are mutually beneficial than they are antagonistic. Thus, symbiosis provides one model for thinking about what a more-than-human design might look like.

The example given at the beginning of this essay, the paduka, is one form of relationship, one kind of symbiosis. Strictly, it is an example of commensalism, in which one organism, or group of organisms (insects or vegetation, in this case), benefits from an act on the part of another organism (a human) who is not significantly harmed or helped. Commensalism is a gift, and it provides a model for all our interactions; would that it was the majority of them. Most of our interactions with the non-human world are, by design if not by intent, competitive or else outright parasitic. Through our use of resources, including water, energy and raw materials, we reduce the common carrying capacity of the Earth, degrading the environment in general and the habitats of individual animals in particular: in evolutionary terms, our fitness is increased, while that of others is lowered. This is competition. It is also, and often, a form of parasitism: when those resources are not renewed, we take from the Earth, and its other inhabitants, without giving back. To fully embrace the more-than-human, we must seek more than commensualism, and become mutualists, wherein our actions, and designs, become a form of reciprocal altruism. Under mutual relations, all participants benefit.

One example of mutualism, which has the feel of more-than-human design, is the living bridges, or Jingkieng Jri, of Meghalaya, a state in north-east India. Meghalaya is one of the wettest regions on Earth, subject to abundant Monsoon rainfalls and devastating floods. Using skills perfected over centuries, the bridge builders of Meghalaya weave the aerial roots of Ficus elastica, the rubber fig, across the course of rivers, implanting them into the opposite bank, and propping them up with bamboo scaffolding. Over time, the roots strengthen, thicken and grow together, to produce sturdy structures which can hold up to fifty people at a time, and withstand crushing torrents which would erase stone, metal and concrete. 19 The ingenious living bridges of India, Zinara Rathnayake, BBC Future Planet, November 2021.[Source]

What transforms this use of natural, living materials into a more-than-human practice is the ongoing relationship between the figs and the bridge builders. First, skilled humans identify the best location for a living bridge. Then they plant and nurture the saplings, which can take over a decade to mature and produce aerial roots. Once the bridge is established, maintaining them is an ongoing process of care and attention, often involving whole villages over generations. As well as literally supporting the community in turn, the bridges stabilise riverbanks, help to prevent landslides, provide passage, habitats and nutrients for other non-human residents of the region, and, like other living plants, absorb carbon dioxide. The whole process is one of weaving; not merely of materials, but of the more-than-human community and all its diverse lifeways, up to and including the atmosphere itself.

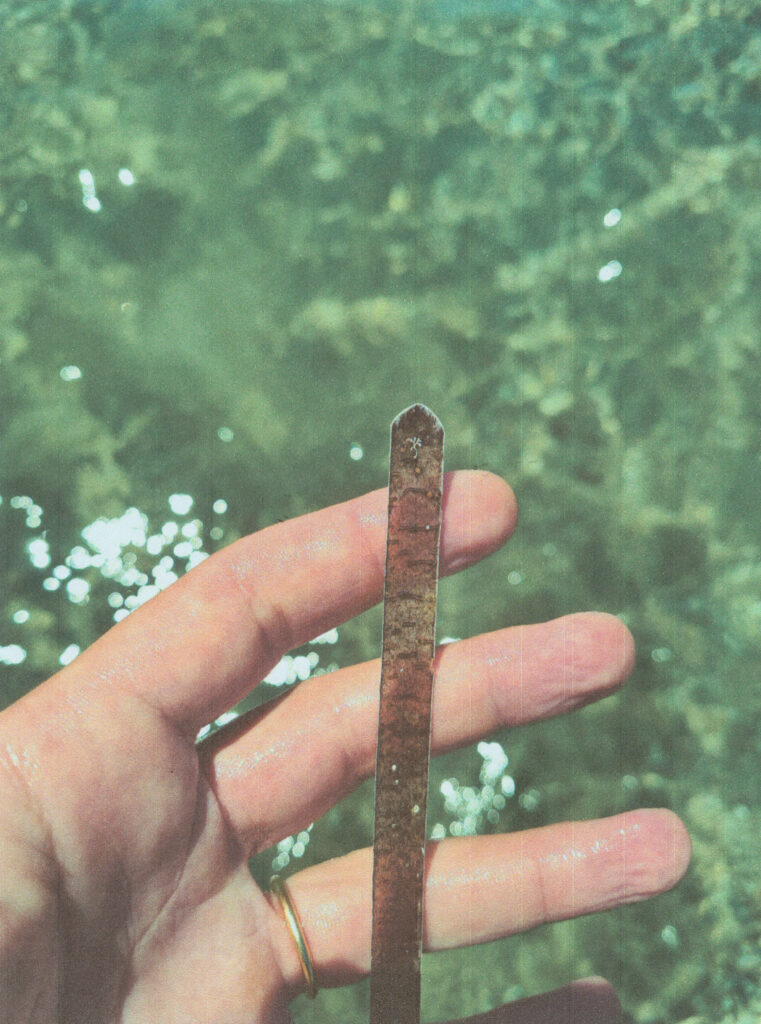

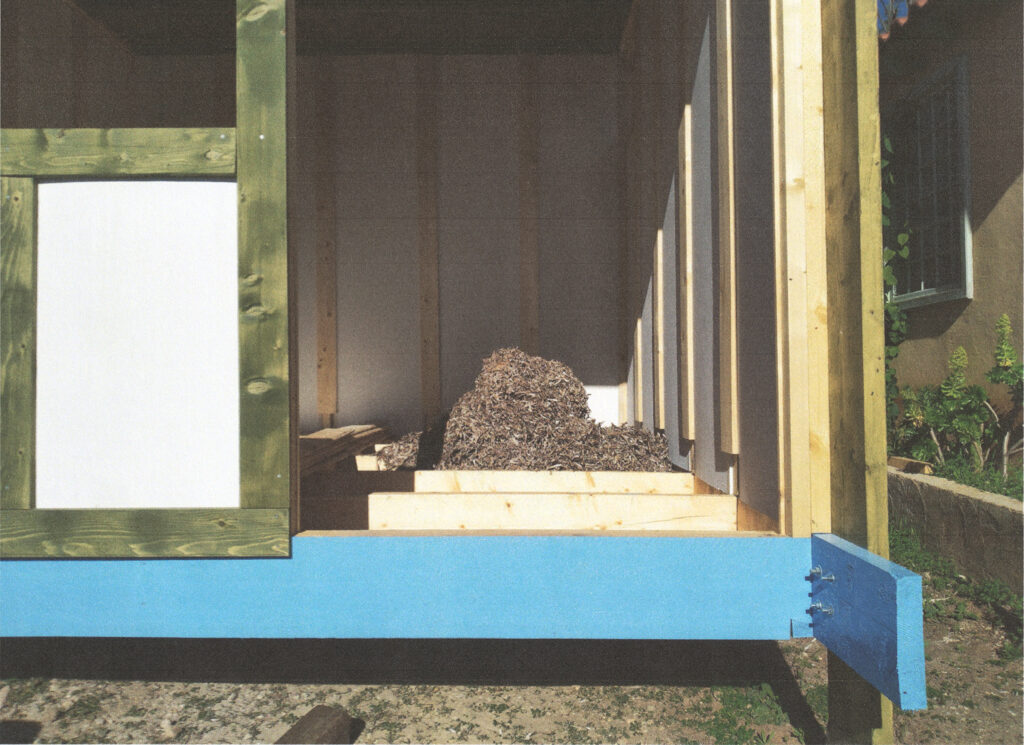

In my own life, I seek to transform commensalism into mutualism through care, attention and practice – not always successfully, and far from ideally – and this too is a tightening of the threads between myself, my community and the Earth. The house I am at present building is based on the designs of Walter Segal, the German-British architect who developed a pattern of self-building for novices, based on the idea that anyone could build a house, and it benefitted everyone to do so. We learn and teach this method of building as a form of relationship-building, and we are adapting it, as best we can, to more-than-human principles. Among these is the use of seagrass, Posidonia oceanica, a flowering plant which grows in vast meadows in the Mediterranean and, in related forms, across the planet, for insulation.

Seagrass has long been used as a natural building material: one finds it stuffed into the walls and roofs of buildings around the Mediterranean, northern Europe and no doubt elsewhere. It is fire-resistant, inhospitable to pests (sorry, pests) and free to gather on beaches, where it piles up every winter as storms wrack shed leaves from the undersea meadows. Living seagrass is vital to marine and planetary ecosystems: seagrass meadows account for more than 10 per cent of the ocean’s carbon storage and, per hectare, draw down more than twice as much carbon dioxide as rainforests. They are a vital part of the planet’s climate regulation system, and they are also the lungs of the ocean, making the vast majority of oxygen found in coastal waters. 20 See James Bridle, ‘The Memory of the Ocean’, in Mediterranean Icebergs. Kyklàda Press, forthcoming.

Yet seagrass is also in retreat, globally. As the direct result of human activity, seagrass meadows have shrunk by up to 50 per cent in the last century alone. Without active reparation, our use of seagrass as material for our designs – without the kind of care and attention embodied by the builders of the Jingkieng Jri – is at best commensalism, and at worst parasitism (even the dead seagrass, left on the beach, performs an ecological function, stabilising the shoreline; take too much, and we risk damaging our environment even further). So we must give back, however we can. At present this deeply limited engagement involves supporting scientific surveys of seagrass meadows in local waters, working on educational programmes on the value of seagrass as material and organism, and actively promoting protection measures and the reduction of damaging practices such as fish farming and ship mooring.

And this, it turns out, is a blessing. There’s a reason I started this essay with a prayer. My engagement with seagrass draws me into the ocean; it has led me to feel, as well as to learn and build. When I swim, bare-legged, through the meadows of seagrass near my home, and sense the caress of long, flat leaves on my skin, and behold the bright, chlorophyllic green of healthy plants which shimmer beneath the waves, I am filled with bodily joy and peace, an organism among organisms, part of the ever-unfolding, autopoetic flourishing of the Earth. This is what it means, how it feels, to be more-than-human.

More-than-human design is political, ethical and embodied. It matters, and it is mattering: it is fundamental to our co-construction of the world, as constituent, entangled elements of Gaia. Like Abram’s magicians, who not only lived at the interface between their human communities and the non-human world which existed all around them, but understood that their powers arose from that interface, that entanglement, so more-than-human design demands of us that we see and feel ourselves and our creations as part of the world’s mutualistic becoming. We all, we must, go on together.