An Embarrassment of Riches

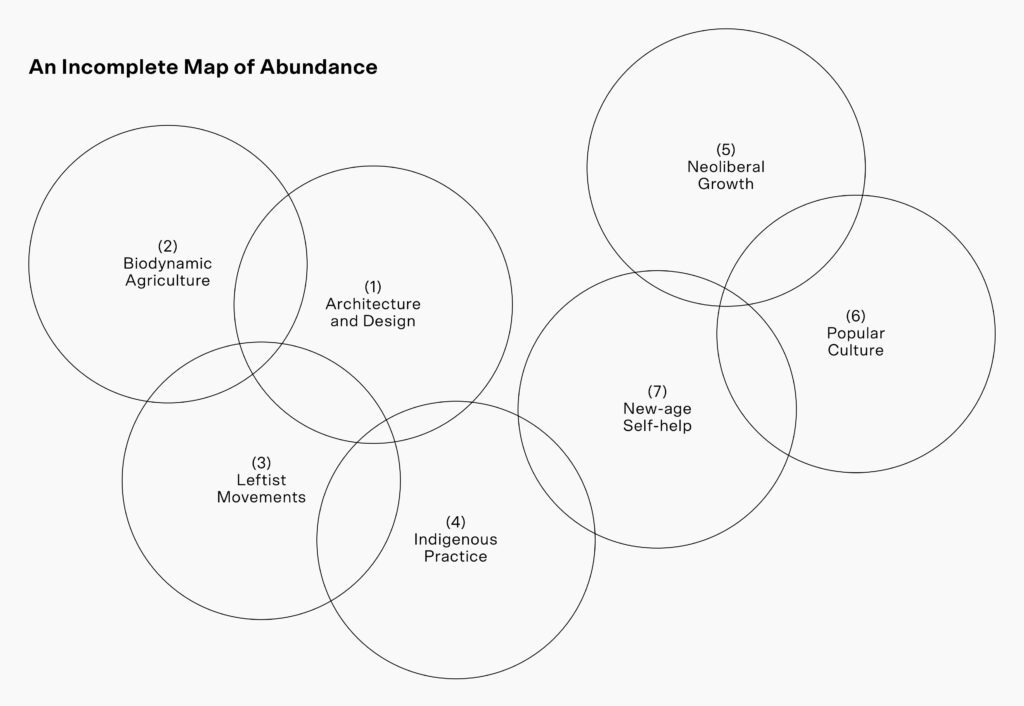

Abundance is a contested idea in political and economic thought. With the term being co-opted to drive growth, the question is what is abundance actually for? Can it be reframed away from the agenda of ‘more’ to a collective vision that sustains all human and non-human life?

In Greek mythology, Tantalus was a mortal king condemned by the Gods to eternal punishment. Odysseus comes upon him in Hades, submerged to his chin in a pool of water, beneath a tree whose boughs are so laden with fruit that they hang low to the water’s surface. When the scorned king tries to drink, however, the water recedes; when he grasps for the fruit, a breeze blows the branches out of reach.

The story serves as the origin of the word ‘tantalising’. It also tells us something profound about our experience of abundance, and of want: that to be surrounded by bounty and unable to enjoy it is worse than to simply lack. In this way, Tantalus’s fate captures the sense of injustice that comes from living in a world and an economy of enormous wealth, but where the planet’s abundance is disproportionately enjoyed, if not hoarded, by a small few and degraded at breathtaking pace.

To experience abundance is to have enough – or, even, more than that. Despite, or perhaps because of, this simplicity, the idea of abundance – and how it is best achieved – has long been contested in political and economic thought. From Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas, philosophers throughout history have frequently invoked abundance as paired necessarily with moderation, seeing the accumulation of wealth for its own sake as an aberration. 1 Thomas Aquinas, The Summa Theologiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (1920), q 118, a.1: Source.

Abundance’s complicated intellectual history has deep roots in the ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ and all that it implied: the colonisation of a vast land overflowing with natural bounty, the escape from Europe’s extravagant combination of monarchic wealth and poverty, the closure of the frontier. ‘The sheer extravagance’ of New England, as James Livingston writes, was a concern for European colonists, who feared it would ‘steer minds away from… the rigors of necessary labour’. 2 James Livingston, ‘Abundance and its Discontents’, Project Syndicate, 7 March 2025, Source. For Karl Marx, meanwhile, abundance looked like liberation from the obligation of wage labour to sustain oneself, allowing man to move from the ‘realm of necessity’ to the ‘realm of freedom’. 3 For an excellent and fulsome exploration of Marxist thought and the idea of ‘abundance’, see Kai Heron, Keir Milburn and Bertie Russell, Radical Abundance: How to Win a Green Democratic Future (London: Pluto Press, 2025). For John Maynard Keynes, securing a widespread abundance would raise the essential question: ‘how to use [one’s] freedom from pressing economic cares… to live wisely and agreeably and well’. 4 John Maynard Keynes, ‘Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren’, The Nation and Athenæum (1930). Even Milton Friedman, hardly a bedfellow of Keynes or Marx, noted in an interview with PBS that his interest in economics was rooted in his experience of The Great Depression and his observation of ‘scarcity in the midst of plenty… of people starving while there are unused resources’. 5 ‘An interview with Milton Friedman, America’s Best Known Libertarian Economist’, Commanding Heights, PBS, Source. From the programmes and ‘five freedoms’ of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to the neoliberal offensive of the 1980s, the major political orders of the twentieth century were, in their own ways, concerned with reconstituting abundance in some form out of periods of decline or crisis.

At some point during the past few decades, we lost sight of the animating force of abundance. This, at least, is the contention of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, whose best-selling book Abundance, published in March this year, has lent the word a renewed political salience. Abundance provides both a straightforward diagnosis of our current political pathologies and a programme for overcoming them. It calls for the construction of a new ‘political order’ based on abundance, defined somewhat vaguely as ‘the state in which there is enough of what we need to create lives better than what we have had’. Achieving this, they argue, need not imply an anti-capitalist revolution, or a radical rethink of economic growth, or much querying of our current economic model at all. Instead, the task is to free ourselves from the ‘blockages’ that presently hold us back.

The political Left, in this account, have focused excessively on redistribution, ‘hobbling’ government with burdensome regulatory obstacles (environmental protection legislation, zoning laws and the like), while the Right wrongly attack government, fixating on tax cuts and placing naïve faith in unfettered markets. In neither case, the authors argue, have political parties of the past several decades done the real work: building the infrastructure and supporting the technological innovation we need.

Critiques of the book abound, many centred on its technocratic policy fixes. These are important criticisms, but Abundance is most telling not in the specifics of its proposals but in the questions it leaves conspicuously unanswered or omits altogether, namely: who, and what, is abundance for? To argue only for clearing the ‘blockages’ holding back an otherwise functional system is to ignore the distributional conflicts inherent to capitalism, and which hold back an abundance that could, and should, be shared by us all.

As Keir Milburn, Kai Heron and Bertie Russell argue in Radical Abundance (2025), capitalism thrives on the imposition of scarcity: while low prices might be good for buyers, they’re typically bad for sellers.

6

See the conversation in this issue: ‘“Radical abundance is something you won’t access under capitalism”

Kai Heron in Conversation with Justin McGuirk’, Future Observatory Journal 03 (2025), Source.

Scarcity is therefore necessary to profit. Take housing: nearly a third of Americans are considered ‘housing poor’, while the median house-price-to-income ratio in the UK has effectively doubled since 1999.

7

Michael Goodier, ‘How UK House Prices Left the Middle Class Behind’, The Guardian, 28 July 2025, Source.

Thousands sleep rough and a record number of children are now housed in temporary accommodation.

8

‘Another Record Number of Children Homeless in Temporary Accommodation after 12% Increase in a Year’, Shelter, 22 July 2025, Source.

In this context, solving the crisis of affordability and ensuring access for all is urgent. Doing so is not as simple as just building more houses – at least not in an economic model where houses are treated not just as places to live, but as financial assets to which many people’s economic security is tethered. In this context, the falling house prices ostensibly meant to follow large-scale construction would be precisely the reason for developers not to build new homes, or for homeowners and landlords to resist them.

A similar logic holds in the energy system. LinkedIn feeds and the pages of specialist press abound with analysts and pundits celebrating how cheap it has become to build renewables. Klein and Thompson similarly remark on how fantastic it is that, at times, renewable energy has been so abundant that consumers are, ‘mind-bendingly’, paid for their usage. Certainly, falling costs are good news for the project of energy abundance. But as economic geographer Brett Christophers has documented, when it comes to investing in new renewable energy, cost is not the most relevant variable for private firms – profit is. 9 Brett Christophers, The Price is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet (London: Verso, 2024).

As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, ours is an economy that ‘thrives by creating unmet desires… the economy needs emptiness’.

Once built, the free gifts of the wind and sunlight should make the operating costs of renewable power negligible, but in a privatised energy system like we have in the UK, cheapness for users stands in direct conflict with the ability for the firms involved to profit. UK governments have sought to overcome this with an array of subsidy mechanisms, the outcome of which is an almost inexorable dilemma between politicians’ desire to keep energy affordable and their need to induce private firms to invest – a conflict that was cast in sharp relief in 2023 when a UK offshore wind auction failed to attract a single bid because the price offered to generators was deemed too low to be profitable. 10 Michael Race, ‘No Bids for Offshore Wind in Government Auction’, BBC News (8 September 2023), Source.

Privatisation of essential services and public assets was sold on the promise that it would create efficiency and, through competition, improve innovation and cut costs. In practice, private for-profit control over the foundations of a decent and dignified life has led to soaring costs, worse services and widening inequality. 11 Sarah Nankivell and Mathew Lawrence, ‘Who Owns Britain’, Commonwealth, Source. These are the products of an inescapable tension: that the fundamentals of a decent life – in Thompson and Klein’s Abundance, housing, energy and health, though we might add care, education, nourishment or any number of vital needs – cannot be guaranteed to all within a model that demands scarcity to function. As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, ours is an economy that ‘thrives by creating unmet desires… the economy needs emptiness’. 12 Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

There is something else missing in the definition of abundance as simply ‘more’ of the good stuff: more houses, more energy, more technology. ‘Abundance’, Klein and Thompson write, ‘is a liberalism that builds’. But abundance in these and other areas will not be achieved in a vacuum, but within the bounds of a finite, if bountiful, planet. The transition to a decarbonised economy is often depicted, in Abundance and even in far more progressive frameworks like the ‘Green New Deal’, as a massive programme of building and replacing things: wind turbines, solar panels, homes, buses, the grid, boilers, heat pumps – the list is long, and these developments are all vital. But this abundant future does not come free of environmental cost. Cutting carbon from our economy hinges on electrification – of transport, of heating, of industrial processes – all of which will require material inputs on a vast scale.

The batteries, for instance, that will fuel the EVs and store energy on the grids of the decarbonised future all demand, for now, lithium, 13 I explore the trade-offs between decarbonisation and extraction at length in an interview with Thea Riofrancos, whose scholarship focuses on the lithium industry, in The BREAK—DOWN, Issue 2, ‘Frontiers’, September 2025, Source. and therefore extraction from the earth. The International Energy Agency predicts that demand for lithium in 2050 will be ten times what it was in 2023. Greening transport by building a system of mass, zero-carbon and affordable transit could enormously reduce this demand, creating far less harm for both people and planet than replacing the billions of cars that currently dot our roads with privately owned EVs. It would also be substantially less profitable. Seen from this vantage, we can recognise abundance, in the words of Aaron Benanav, not as a ‘technological threshold, but a social relationship’. 14 Aaron Benanav, Automation and the Future of Work (London: Verso, 2020).

Part and parcel of genuine abundance is asking not only where we need more, but also where we need less.

Since the end of the Second World War, the graph of global economic growth has trended, with a few brief stutters, ecstatically upward. If this might be considered a measure of abundance, then humankind presently enjoys the most abundant period in our collective history. During this time, often referred to as ‘The Great Acceleration’, the number of vehicles has risen twentyfold, reaching over 1.6 billion in 2024. The production of plastics has increased three hundredfold. Primary energy use has more than quintupled. Livestock now make up 62 per cent of all mammal biomass on the planet, while wildlife accounts for just 4 per cent. Perhaps most urgent of all: nearly half of all man-made carbon emissions have been released in the past three decades alone. The ability to produce and live in this way is reaching its end, as climate impacts mount and the biodiversity that sustains all life continues its rapid decline.

While there is some evidence of individual countries’ ability to ‘decouple’ GDP growth from carbon emissions, the rate of this decoupling in absolute terms is nowhere close to the rate needed to limit global temperature change to 1.5 or even 2 degrees. There is considerably less evidence for our ability to decouple economic growth from material and resource use, with efficiency gains broadly wiped out by rising affluence. Part and parcel of genuine abundance is therefore asking not only where we need more, but also where we need less: disposable electronics accumulating in landfills; the castaways of a fast fashion industry heaped in markets in Ghana. Here design has a clear role to play in supporting the longevity and circularity of the things we build and produce, but it urgently needs support from policymakers – design is equally constrained by the pressures of the profit motive, particularly in a vacuum of support from a government increasingly shy of environmental regulations and single-mindedly bullish on growth.

Perhaps the most urgent question about abundance is also the most basic, namely: what is it for? The answer we find woven throughout the long intellectual history of this idea is freedom – freedom from want, freedom from the brutishness of the ‘state of nature’. But while abundance may enable freedom, it does not guarantee it. There is, as political philosopher Alyssa Battistoni writes: ‘a paradox of affluence and freedom under capitalism – that domination persists even amidst material abundance’.

The relationship between abundance and freedom is not as straightforward as material affluence providing liberation from the insecurity of the state of nature. 15 Pierre Charbonnier, Affluence and Freedom (Cambridge: Polity, 2021). Under capitalism, the abundance we produce creates a freedom that is deeply partial. It is the freedom to consume in a market while being compelled to work to live. It is a freedom based on the exploitation of people and ecosystems often hidden from the view of those residing in Europe and North America. As such, it is not only incomplete but incredibly fragile.

A central thread running through Abundance is that at some point our politics stopped looking towards the future. Diagnoses of when or why abound, though most seem to situate the beginning of the end of history sometime in the 1970s, when economic decline ushered in the period of neoliberalism.

‘Make America Great Again’ may be the most salient example of this giving up on the future, apt not only because it constructs its political project through the rearview mirror, but because it is lifted from President Raegan and the dawn of the end of history itself. But it hardly stands alone. Everywhere, nostalgia pulses through political messaging, eliding any vision for the future.

This ‘slow cancellation of the future’, as Marxist philosopher Franco Berardi terms it, spells the end of many myths that have long defined our ideas of progress, from the ‘linear development of welfare and democracy’ to the ‘technocratic mythology’ of innovation and scientific advancement as universally guaranteed and good. The advancing climate and ecological crises make this disruption only more acute, giving many of us the sense of a future foreclosed.

In another telling of the myth of Tantalus, the doomed king has instead drawn the ire of the gods by asking to live as abundantly as them. Bound by oath, Zeus grants Tantalus a vast feast. However, as punishment for Tantalus’s insolence, Zeus suspends a large rock above his head, so that he is prevented from ever enjoying the bounty out of constant fear that it may fall. We might see in this version of the story echoes of our own predicament: a fragile abundance available only to some, whose production has left us, and our future, incredibly vulnerable.

In a world defined by indefensible inequality and, for so many, profound lack, reclaiming the future with a programme centred on abundance is urgent. But abundance on its own will mean little if its fruits are not more equally shared. Just as urgent, then, will be to ask not just how we can produce abundance, but for whom and to what end? How can abundance be made collective? How can it be secured while minimising our impact on the ecological systems that sustain both human and non-human life? And what forms of abundance are truly required to live a good life? Most urgent of all will be to build a vision of the future around what abundance is truly for: a collective freedom not predicated on the domination of others, or the Earth.