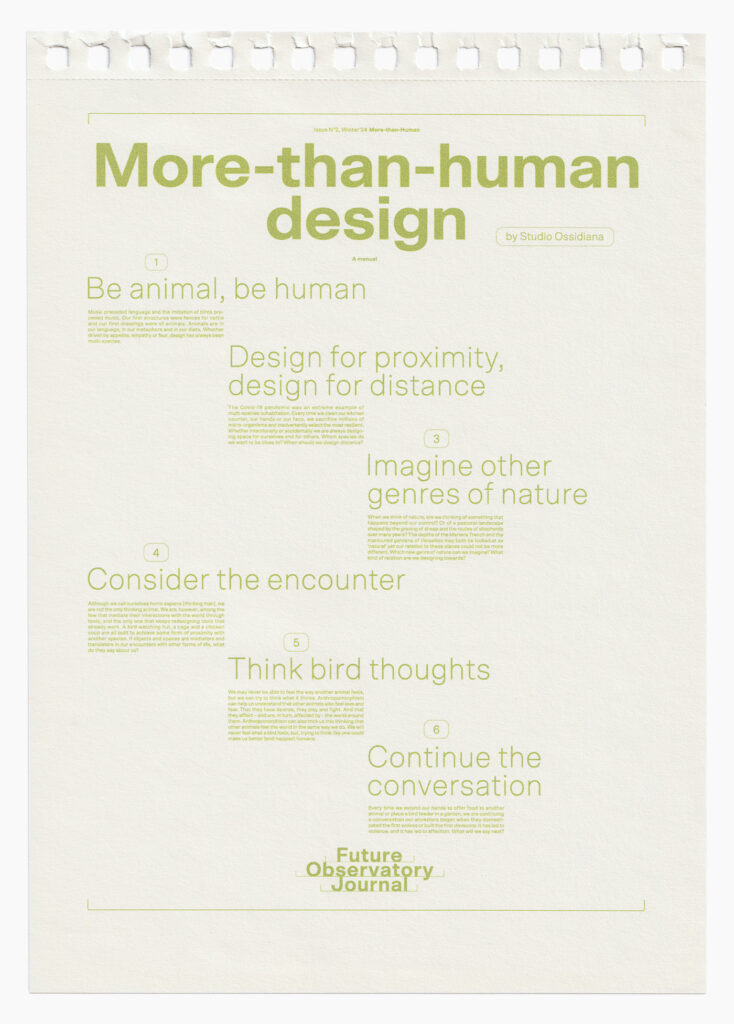

A Manual for More-than-Human Design

This manual provides a practical set of guidelines, precepts and pieces of advice for designing with other species in mind. You can also print it as a poster and stick it on your wall

Editor’s note

For each issue of the Future Observatory Journal we commission a manual. This is intended as a practical set of guidelines, precepts or pieces of advice from design and research practitioners who work in dialogue with the issue’s theme. The manual can be read online, or printed out and stuck on your studio wall in the form of a bespoke poster designed by Studio Airport.

This issue we commissioned Studio Ossidiana, an award-winning practice working at the crossroads of architecture, design and landscape. Led by Giovanni Bellotti and Alessandra Covini, Studio Ossidiana projects such as The Birds’ Palace in Amsterdam or Büyükada Songlines in Istanbul often host both humans and non-humans in urban public spaces.

Be animal, be human

Music preceded language and the imitation of birds preceded music. Our first structures were fences for cattle and our first drawings were of animals. Animals are in our language, in our metaphors and in our diets. Whether driven by appetite, empathy or fear, design has always been multispecies.

Design for proximity, design for distance

The Covid-19 pandemic was an extreme example of multispecies cohabitation. Every time we clean our kitchen counter, our hands or our face, we sacrifice millions of micro-organisms and inadvertently select the most resilient. Whether intentionally or accidentally we are always designing space for ourselves and for others. Which species do we want to be close to? When should we design distance?

Imagine other genres of nature

When we think of nature, are we thinking of something that happens beyond our control? Or of a pastoral landscape shaped by the grazing of sheep and the routes of shepherds over many years? The depths of the Mariana Trench and the manicured gardens of Versailles may both be seen as ‘natural’ yet our relation to these places could not be more different. What new genres of nature can we imagine? What kind of relation are we designing?

Consider the encounter

Although we call ourselves homo sapiens [thinking man], we are not the only thinking animal. We are, however, among the few that mediate their interactions with the world through tools, and the only one that keeps redesigning tools that already work. A bird watching hut, a cage and a chicken coop are all built to achieve some form of proximity with another species. If objects and spaces are mediators and translators in our encounters with other forms of life, what do they say about us?

Think bird thoughts

We may never be able to feel the way another animal feels, but we can try to think what it thinks. Anthropomorphism can help us understand that other animals also feel love and fear. That they have desires, they play and fight. And that they effect – and are, in turn, affected by – the world around them. Anthropomorphism can also trick us into thinking that other animals feel the world in the same way we do. We will never feel what a bird feels, but, trying to think like one could make us better (and happier) humans.

Continue the conversation

Every time we extend our hands to offer food to another animal or place a bird feeder in a garden, we are continuing a conversation our ancestors began when they domesticated the first wolves or built the first dovecote. It has led to violence, and it has led to affection. What will we say next?