From the Portfolio

As well as publishing and curating, Future Observatory funds design research projects at different scales across the UK. From the Portfolio brings together a group of objects emerging from our funding portfolio which respond to the theme of the issue.

FO_Porfolio_06

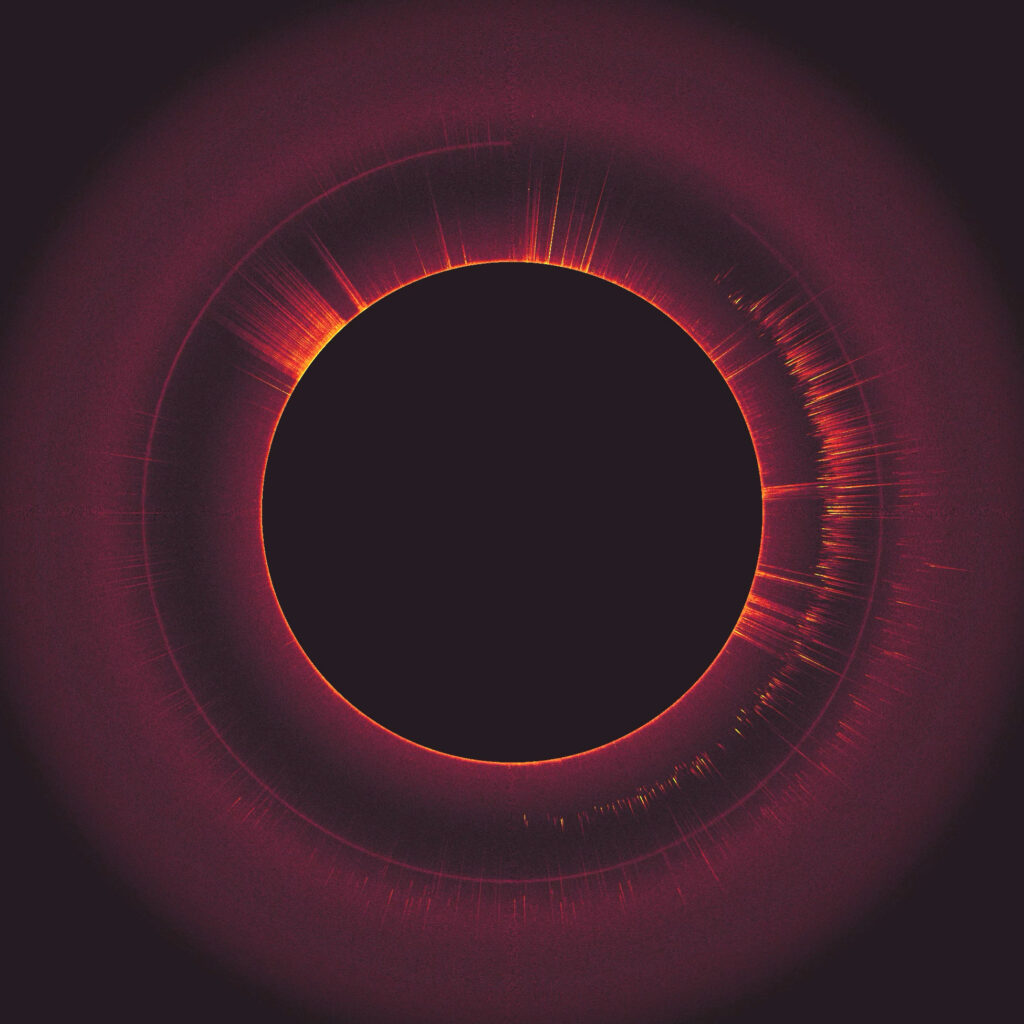

Radial Spectrogram

Design/Research: Lancaster University, Slough Borough Council

Funding stream: Design Exchange Partnership

Eyes closed and ears open; what do you hear? For those of us in urban environments, it’s probably the sounds of human activity: engines revving, construction workers drilling and people shouting over sirens and horns. But what about the noises of nature in the city; the croaks, chirps and chattering of other species and lifeforms? What might we learn if we could tune into this more-than-human soundscape?

These are questions being asked by researchers at Lancaster University as part of their Future Observatory Design Exchange Partnership project. Drawing on the fields of acoustic ecology and bioacoustics, the university’s design research hub is exploring ways in which the visualisation of sound could help us become more sensorially attuned to urban biodiversity.

Working closely with the local council and community organisations in Slough, south-east England, Lancaster’s research team has been collecting audio material from the town’s urban forests. This is then being translated into radial spectrograms – visual representations of audio signals reminiscent of the iris in a human eye.

Follow the illuminated edge of the ‘pupil’ and a landscape comes into view, one which visualises the urban soundscape as it unfolds from day through dusk into twilight. Each brightly lit spike marks a singular sound event, indicating the presence of a vocal organism; in this case, the stirring of insects at sunset, followed by the feeding calls of bats as night falls. The hidden voices of biodiversity are revealed, layer by layer, and the spectrogram immerses us in their visual translation.

What does it mean to be able to watch the stridulation of insects or survey the echolocation of bats? And how might our relationship with these species change if we could perceive their presence in our urban environments? By making visible that which is out of sight – and perhaps also out of mind – Lancaster’s research brings biodiversity into our perceptual fields. In doing so, it invites us to pay a little more attention not just to our urban landscapes but also to the other species with whom we share them.

(Text by Leilah Hirson-Comley)

FO_Portfolio_07

Fables for Our Time

Design/Research: Space Popular and Shumi Bose

Funding stream: Future Observatory commission

Once upon a time, humans could turn to Goldilocks or the Hare and the Tortoise for lessons on ethics and discipline. Fairytales and fables shared teachings and moral guidance that reflected the cultural preoccupations of their time, but whose advice should we heed to make sense of the world, with its planetary emergencies, today?

This is a question being picked up by design duo Space Popular and architecture writer and curator Shumi Bose, who have identified that the climate crisis is also a crisis of imagination. ‘It is hard to convey the immensity or extent of interconnected events that play a role or are affected by ecological change,’ they explain. As a result, we need new forms and modes of storytelling ‘to imagine how we might design today’s planetary possibilities together’.

Their new work Fables for Our Time is a kaleidoscopic frieze of multispecies activity, commissioned by Future Observatory and installed at the Design Museum, which invites visitors to imagine humans in assembly with more-than-human ecosystems. Viewed from afar, across the museum’s atrium, the frieze shows three distinct landscapes: a buzzing flower meadow, a resilient coral reef and a lively mycelium network. Up close, the distinct lines of the landscapes lose their focus as clusters of emoji-like pictograms come into view. These icons – starfish, batteries and tractors to name only a few – don’t just provide the artwork with its colour and texture, they are also ‘symbols of how humans have learned from this environment, but also how we can be a threat’, explains Bose.

In front of each scene are fantastical characters who appear to guide viewers like storytellers. For example, beneath the meadow, the guides congregate to sing songs about the delicate balance of the pollinator’s world; a group of coral gardeners are seen tending to the reef; and under the toadstool mushrooms, daydreamers grasp at microphones to share news via the ‘wood wide web’.

Left to our own devices, humans may not have the means to see the planet through to a happy ever after. Fables for Our Time reminds us that the flourishing of humanity has always relied upon the lessons nature has to impart, we just need to remember how to listen.

(Text by Lila Boschet)

FO_Portfolio_08

Sero

Design/Research: Feifei Zhou

Funding stream: Future Observatory Fellowship

For thousands of years, fishing nets and traps have been made from locally sourced plant materials: spruce root fibres and wild grasses by Americans on the Columbia River, willow by Karelians in Finland and flax by Ancient Egyptians on the Nile. Despite vast geographical distances between them, there were often marked similarities in the forms and intelligence of these vernacular infrastructures. Unfortunately, the homogenisation of these infrastructures due to the mass production of nylon nets for the commercial fishing industry is endangering both traditional craftsmanship and the biodiversity of our oceans.

Future Observatory Fellow Feifei Zhou has been researching a disappearing population of artisan fisherfolks in Kupang Bay who weave fishing traps called sero from the leaves of the local Gewang palm. Like many vernacular crafts, the process of making the sero is not tangibly documented but passed down from one generation of craftsperson to the next. Through drawing, filming and mapmaking, Zhou’s work evidences the making, installation and use of the sero as a life-sustaining practice for humans and non-humans alike. ‘We tend to overlook the intelligence of vernacular infrastructure and craftsmanship in favour of prioritising modern techniques,’ she says. The sero is constructed with an open-weave technique, contrasting the non-porous structure of modern nylon nets, a design choice that allows young marine life to escape, thereby maintaining a healthier marine ecosystem.

Marine life is not the only victim in the face of extractive commercial fishing practices. Zhou explained that the placement of the sero was designated based on agreements between families that ensured households would yield relatively equal catches. However, the indiscriminate nature of commercial fishing nets means traditional fisherfolk are struggling to feed their families. Increases in commercial fishing practices, as by the Indonesian government, disrupt an intricate, old network of more-than-human relations in Timor. Marine ecosystems and the coastal communities they support and live alongside are breaking down but, through analysis of the relations the sero once upheld, Zhou’s work illustrates a ‘vast, living zone where more-than-human lives are sustained and able to thrive’, and reminds us of the many-layered intelligence of vernacular design techniques.

(Text by Jennifer Cunningham)

FO_Portfolio_09

Dovecote for London

Design/Research: James Peplow Powell

Funding stream: Design Researchers in Residence

There is one pigeon to every three Londoners but their life in the city is defined by spikes, nets, baits and predators. The Greater London Authority and Transport for London opt for ‘management strategies’ based on spatial exclusion but, try as they might, the pigeon will not be evicted.

It wasn’t always this way – pigeons were once a close collaborator of humans. The birds were celebrated for their homing instincts as messenger pigeons and for their nutrient-rich guano – poo – which has been used as fertiliser since the 4th century CE.

Exploring these tensions is Dovecote for London, the ongoing research enquiry by architect, multispecies designer and former Future Observatory Design Researcher in Residence James Peplow Powell. His project proposes the strategic placement of dovecotes – homes for pigeons – on bridges along London’s transport network. The repeatable module would attach to these structures, enabling Transport for London (TfL) to manage the population and even benefit from the guano. Ceramic niches provide external perches, and a timber lattice frame creates internal roosting shelter where the guano can be contained, collected and redistributed to urban farms. By reviving the near obsolete typology of the dovecote, Peplow Powell reimagines animal husbandry for the 21st-century city, re-framing the human–pigeon relationship from one of exclusion to care.

For the next iteration of Dovecote for London, Peplow Powell intends to move from the bridge to the laboratory while continuing to work with the pigeon as a gateway to understanding changes in urban ecosystems. Scientists have found that pigeons in cities have darker feathers on account of metabolizing heavy metal pollutants, meaning they are adapting to our urban environments on a cellular level. Alongside environmental chemists and soil microbiologists at Sheffield Hallam University, Peplow Powell is exploring the role of the pigeon in future urban nutrient cycles, testing the fertility content of urban pigeons’ guano and its potential impacts on the soil. From carrier pigeons to the carrier of messages about our toxi-polluted worlds, what else can we learn from these birds to take into future urbanism and more-than-human care?

(Text by Alys Hargreaves)

FO_Portfolio_10

Ipomopsis Hybrid

Design/Research: Eliza Collin

Funding stream: Design Researchers in Residence

What happens to flowers when snow melts earlier every year, less rain falls and the heat of the summer sun intensifies?

Dr. Diane Campbell, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist at UC Irvine, has been studying the wildflowers scarlet gilia (Ipomopsis aggregata), slender skyrocket (Ipomopsis tenuituba) and their hybrids for over three decades. To gauge the impact of a changing climate on these species, and whether they will survive the next 100 years, Campbell’s lab has been simulating future weather conditions at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL) in Colorado. Every year of collected data gives a more accurate vision of the future Rocky Mountains ecosystem, yet they have never used the data to really sense the reality of these changes. Working with Campbell and the researchers at RMBL, as well as a botanical illustrator and an animator, Eliza Collin, a former Future Observatory Design Researcher in Residence, has begun to decipher the data on the changing Ipomopsis hybrids and visualise the future wildflowers of the Rocky Mountains.

The resulting video shows 100 years of evolution in ten seconds; evidencing just how stark the effects of changing weather patterns may be on the shape of the Ipomopsis flower. But what do these changes reveal? As the video plays, the petals of the wildflower gradually shrink and widen, a change impacted by ever-drier soils in the Rocky Mountains. Adapting both the form and thickness of the leaves allows the plant to optimise its water usage, and therefore to survive lengthier dry periods following the onset of earlier Springs. But water isn’t the only deciding factor in the persistence of the plant. The petals shrink and widen, revealing six pollen-covered anthers. Displaying the anthers above the top of the petals makes the flower more attractive to pollinators, the decision-makers in the natural selection of this wildflower. Of all the Ipomopsis variants studied by scientists at the RMBL, their research predicts that this hybrid species, capable of climate-responsive shape shifting and bargaining with local moths and hummingbirds, will be the only one to prevail.

Although human actions cause climates to change, it is the elements and atmosphere, insects and birds, soil and plants that will determine what will still exist in an ecosystem in one hundred years. By simulating the future of the wildflower, Eliza’s work not only helps us to understand the evolution of plants and their pollinators in a future Rocky Mountains ecosystem, but begs the question: can they keep up?

(Text by Jennifer Cunningham)