From the Portfolio

As well as publishing and curating, Future Observatory funds design research projects at different scales across the UK. From the Portfolio brings together a group of objects emerging from our funding portfolio which respond to the theme of the issue

FO_Portfolio_11

Angora rabbits

Design/Research: London Metropolitan University, London Borough of Islington

Funding stream: Design Exchange Partnership

Photo © Matthew Kaltenborn / Future Observatory Journal

What comes to mind when you think of a rabbit? Perhaps it’s your family pet, a magic trick or the Easter Bunny. For London Metropolitan University and the borough of Islington, rabbits are a starting point for their Design Exchange Partnership, exploring a neighbourhood-scale commons for fibre production.

As researcher Alice Holloway explains, angora rabbits are not only impossibly cute but they are also prolific grazers, and their fur, when sheered and spun into yarn, becomes a highly valuable commodity: angora wool. But how can thinking holistically about rearing and shearing angora rabbits transform a neighbourhood? From local governance to local life, Holloway and fellow researcher Torange Khonsari have begun mapping the potential benefits of introducing these rabbits into the green spaces of council estates. More specifically, by building rabbit pens on these spaces across Islington, angora rabbits would be integrated into the fabric of the neighbourhood. In addition to the mental health benefits of being outside, interacting with more-than-human life, the health and biodiversity of these plots would be maintained naturally thanks to the rabbits’ grazing habits. Holloway and Khonsari have even mapped the possible opportunities associated with upskilling the community to participate in the textile supply chain: from spinning the fibre to designing and producing angora products. Under a commons model, what starts off as a straightforward land-use proposal is packed with co-flourishing potential for stakeholders across the community.

This approach to stacking enterprises, though far from typical in local government, is standard practice in permaculture agriculture. Holloway explains that, instead of depleting resources through layers of activity, these enterprises are designed so that ‘each one feeds and regenerates the next’. Given the state of councils across Britain today – stretched for resources or in some cases declaring bankruptcy – taking agricultural principles out of the pasture and into government strategy could offer an alternative to our monocultural approach to policy and resources.

It is still early days, but Khonsari and Holloway’s research is beginning to identify those future roles required to implement this textile commons – from rabbit minders and community spinners, to the locally appointed angora-jumper attaché, to bringing the Islington Borough to Liberty of London. Each would have a hand in co-creating a new typology for an eco-social textile economy.

FO_Portfolio_12

Harmless Henry hoover

Design/Research: Laura Lebeau

Funding stream: Design Researchers in Residence

Photo © Andrea Conde Pereira / Future Observatory Journal

The smiling red face of the Henry vacuum cleaner seems to pop up everywhere – from homes and offices to school corridors and building sites. This is no coincidence, because behind Henry’s big eyes and cheery grin is an appliance built to last. Numatic – the Somerset-based company that produces Henry – has forged a reputation for reliability with simple, unchanging designs, as well as the easy sale of replacement parts for DIY repairs and a growing second-hand market for used and refurbished Henrys.

This culture of reuse, repair and regional production captured the imagination of Laura Lebeau during her 2024/25 residency at the Design Museum. While examining the environmental impact of everyday electronics, Lebeau began to question whether a truly ‘harmless’ appliance could exist. What would our everyday products look like if made entirely from renewable materials, absent of microplastics and toxic ‘forever chemicals’? Was it possible to manufacture durable everyday appliances with regional sourcing and bespoke manufacturing practices, breaking free from existing global supply chains?

These questions were tested through Harmless Henry, a prototype that reimagined the classic vacuum cleaner design. At first glance, it looks familiar – red body, nozzle nose, cartoonish eyes – but on closer inspection its irregular surface texture and lopsided smile challenge the material palette we have come to expect from our mass-produced electronic devices. In this new, more harmless form, Henry’s polypropylene shell has been replaced with 3D-printed ceramic, his TPE tube reconstructed from folds of recycled paper, the thermoplastic filter is now woven from hemp, wax thread and cork, and his wheels have been refashioned from mycelium and felled urban tree ash. Grounded in local making, each component has been sourced within 100 miles of Central London and retains its natural finish. ‘The aim’, Lebeau explains, ‘is to make the hidden material realities of familiar objects like Henry more visible.’

A harmless appliance may not be as pristine and smooth an object as its mass-produced counterpart, but for every lump and bump of this prototype, users are called to reappraise the supply chains we take for granted and reconsider whether the uniformity of mass production is the design brief we really need.

FO_Portfolio_13

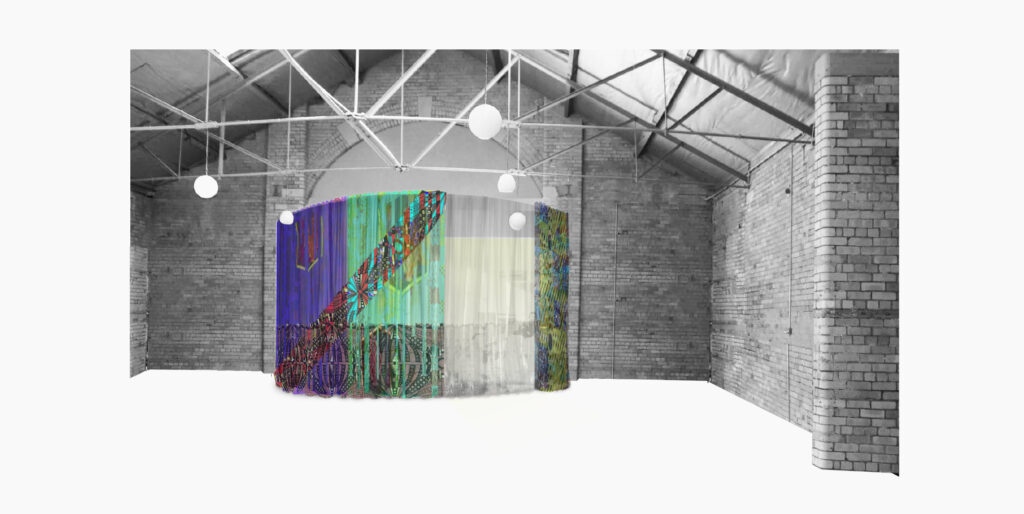

Energy curtain

Design/Research: Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield and District African Caribbean Community Association

Funding Stream: Design Accelerator

Render by Anne Wakeford Holder / Future Observatory Journal

The Sheffield and District African Caribbean Community Association (SADACCA) is a busy building, and on any given day, while groups of women sew together in one room, an intergenerational class might be cooking Jamaican Saturday Soup in the next. The space itself is vulnerable: in the G Mill, the building’s event hall, fire safety regulations demand that the wide entrance doors remain open at all times. The temperature inside can fall as low as -5 degrees in the winter, rendering the space functionally useless. In areas like Wicker and Spital Hill, where the Community Association is based, and where the threat of fuel poverty looms large, practical energy solutions are needed.

This was the challenge taken up by a team of design researchers from Sheffield Hallam University who, working alongside associates from the community, are seeking to help transition the area into a grassroots Positive Energy District. Such districts are defined as neighbourhoods that have reached net-zero emissions by generating their own renewable energy. Pilot projects across Europe typically look to achieve this goal through engineering ingenuity, often developing glossy, private ‘smart grids’. But how can a community fighting to keep its buildings standing and energy bills paid achieve the same goal?

The solution, developed by the project team, starts with a cozier prototype: a curtain. Framed as a Design Accelerator – a small-scale reactive project that supports engagement between local communities and the general public – the team have enlisted the Association’s women’s sewing group, as well as community members and local artists, to co-produce a heavy, fire-resistant curtain. Made up of a patchwork of fabrics from the African and Caribbean diasporas, the curtain will tell a story of the history of energy within the community. More pragmatically, once connected to an overhead rail, the fabric will be drawn across the G Mill doorway, retrofitting the space to better retain heat.

The project team believes that even if ‘energy infrastructures’ may be lacking in the building, ‘energetic infrastructures’ within the Association – the solidarity and self-organisation that sustain it – are abundant. The curtain is a product of this belief, and it distils a Positive Energy District down to its essence: a place where social wellbeing – a good life for all – is not at odds with energy transition, but is its driving force.

FO_Portfolio_14

Mosaic Landscapes

Design/Research: Design HOPES

Funding stream: Green transition ecosystem

Image courtesy of Design HOPES

NHS Scotland operates more than 100 acute-care hospitals, around 880 GP surgeries, 60 community hospitals and countless ancillary facilities, all in some way or another connected to public health. Surprisingly, it is also custodian to one of the biggest land estates in Europe, and while much of this space is populated by its buildings, over half of its total 1,572 hectares is made up of forests, bogs, burns, parks and gardens. Encouraging more communities to use and develop this green space is central to NHS Scotland’s Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy, part of its wider plan to reach net zero by 2040.

How this happens is a question being asked by one of the Design HOPES project teams (part of the Future Observatory Green Transition Ecosystem) as they look to shift the thinking about hospital grounds, away from the more conventional spaces of surgical theatres, wards and consulting rooms, towards open spaces that can support a different kind of environment for health and wellbeing. To facilitate this thinking, design researcher Laura MacLean and her team, along with NHS Highland, have created a boardgame that gives everyone a voice in co-designing these shared outdoor spaces.

The game itself is called Mosaic Landscapes and is played in two parts. In the first round, players role-play as a hospital patient, staff member or visitor and, with their character’s needs in mind, negotiate which nature-based interventions are most important to their site from 32 wooden landscape pieces (among them, nature trails, beehives, wilderness therapy, a bogland, car park and a bench). In the second round, players come together to write a collective design statement, defining how these interventions could transform their site. A live site in Dumfries and Galloway is currently playing the game, allowing locals, patients and staff to collectively define how the land might benefit everyone who uses it.

The development of Mosaic Landscapes is connected to the development of a more holistic healthcare service, one invested in the wellbeing of people as well as the environment. As Laura said: ‘Making these stronger outdoor spaces for communities and socialising to happen not only supports people’s health and wellbeing, it feeds into a wider plan for preventative health in Scotland.’ By taking healthcare outdoors, Mosaic Landscapes shows how individuals and communities can flourish alongside the natural spaces that they tend, wander through and protect.