From the Portfolio

Future Observatory research projects; as well as publishing and curating, Future Observatory funds design research projects at different scales across the UK. From the Portfolio brings together a group of objects emerging from our funding portfolio which respond to the theme of the issue.

FO_Porfolio_01

Wet spinning machine

Design/Research: Mourne Textiles and Ulster University

Funding stream: Design Exchange Partnership

Harvest, scutch and heckle the flax plant and it is ready to spin into linen yarn. This was once a common practice in Northern Ireland, but the rise of synthetic fabrics in the 1950s curtailed the region’s history of field-to-fabric linen production. Spinning equipment was shipped away to new textile hubs in South Africa, Portugal and China, and with them went the linen skills and knowledge needed to keep those practices alive. But in 2023 when Mario Sierra, the director of Mourne Textiles, a traditional weaving mill, discovered a suite of industrial spinning equipment in a derelict linen mill, it set in motion a project that might just revive Irish linen.

What Sierra stumbled upon is not simply a relic of a bygone industry. Each of the seven machines – from the wet ring spinner to the spreader, doubler and the hackler – plugs a gap in the linen production supply chain. If restored, Irish linen is back. But the overhaul of these bulky and intricate machines is no small feat. Take the Wet Spinning Machine. This machine dissolves flax fibres in a liquid spinning solution that is then extruded into continuous filaments. The environment of the machine plays a part in this process too. It needs to be 25 degrees and high humidity so that liquid solution can bind the fibres together; the machine constantly pulls and elongates the flax fibres until they are twisted and wound on the bobbin. The Spinner is in a rickety state; its frame is worn and the motor responsible for heating the spinning solution is in dire need of replacement. Removing the rust and replacing the missing parts is only a part of revitalising the supply chain. Each machine – from the Shuttle Loom, Spinner, Spreader, to the Doubler and Hackler – requires knowledge from craftspeople to operate. Alongside the restoration, the project team, which involves researchers from Ulster University working on a Future Observatory Design Exchange Partnership project, are connecting with expert spinners to record and pass on their knowledge to a new generation. ‘If everything goes according to plan’ reports Anna Duffy, researcher at Ulster University ‘we will have some wet spun linen by the summer.’ Although the machinery is vintage, this mini-mill and the self-sustaining system it enables, where linen can be farmed, processed and spun in Northern Ireland, is fit for an ecological future.

(Written by Lila Boschet)

FO_Porfolio_02

Patacel yarn

Design/Researcher: Fibe and Imperial College London

Funding stream: Design Exchange Partnership

You say potato, I say … regenerative design opportunity? Idan Gal-Shohet is co-CEO and one of the design engineers behind fibe, a start-up transforming the humble spud into the future of fashion. Following years of R&D, fibe has developed a method of extracting fibres from potato plants which has the potential to transform the materials we currently use for clothing. Cotton, for example, is as common as a white t-shirt but growing the cotton plant is water and carbon intensive, it takes up a lot of land (2.5% worldwide, to be exact) and produces considerable waste. With that in mind, what would it mean if fibres for clothing could be extracted using waste streams from plants already fulfilling other purposes, like food crops?

It is this proposition, as well as funding as part of a Future Observatory Design Exchange Partnership, that brought fibe to Jersey, an island off the south coast of England. Beyond the cliffs and lagoons lining the shores of the island, 51% of the land in Jersey is agricultural, most of which is used to grow the famous Jersey Royal potato. As it stands, potato stems, the above ground plant of the crop, are a waste stream of the harvest. Inedible and difficult to compost, the stems are left to rot while the vegetable is sent off to star in roast dinners across the UK.

After extensive research, fibe have arrived at Patacel, a yarn made from those wasted stems developed using a novel bio-mechanical fibre extraction process. Patacel is an important milestone for the company, proving that potatoes can produce a fibre suitable for textile production, as well as demonstrating that ‘we could replace the land used to grow cotton with potato crops instead’. As Gal-Shohet tells it, ‘potatoes grow in the same places where we already manufacture textiles, like India, China and Portugal, so we can create local supply chains with local farms there too’. It’s only the beginning for fibe, but these green shoots may point towards a green transition that builds on resources already in place. If all goes to plan, by the time spring/summer 2030 rolls around, you might be sporting a 100% Jersey Potato t-shirt.

(Written by Lila Boschet)

FO_Porfolio_03

Ogma typeface

Design/Research: Isabel Lea

Funding stream: Design Researchers in Residence

In Cornish, the word troze refers to the sound of water breaking on the bow of a boat. In Irish Gaelic, a sabhsaí is someone who works outside no matter how bad the weather is. Words such as these capture a world; they describe a confluence of specific environments, weather, sounds and labour. Words like these aren’t common in English and it’s perhaps no surprise that the lingua franca – fit for business on a global scale – is not so preoccupied with phenomena like gurnall (Cornish); the change in run of a stream caused by shifting of sand. Yet as climate breakdown accelerates, revealing just how intertwined the human and natural world are, it may be worth paying renewed attention to languages perceptive to environmental nuances. How might these words, and the values they engender, be part of an ecological epistemological shift?

For graphic designer, typographer and former Future Observatory Design Researcher in Residence Isabel Lea, the answer comes down to the letter. In her typeface Ogma, each stroke, curve and serif is culturally implicated, down to the decision to base her typeface on the Celtic alphabet rather than the Latin, which in the West is considered the default. Lea began her design process by hand-drawing each character with a parallel pen to capture the movements and shapes that traditional calligraphic tools imbue in the Celtic scripts. In the digital drawing, you can see how the Welsh ‘ff’ diagraph stroke weight changes where a pen would curve, and how the line joining the ff together is top and tailed at an angle, mimicking the effect of a nib ink pen.

Inspired by Celtic traditions, from calligraphy tools to place-based words, Ogma centres previously side-lined environmental know-how. From coasts to pastures to mountain ranges, Celtic languages are a window into a way of life that takes a holistic approach to the lives that humans live in relation to their environment, or what the Cornish call bownans (the lifetime that you occupy in relation to the wider scheme of things). While sometimes overlooked, typefaces are the lenses through which we see written language and, by extension, make meaning. From the instructive authority of Times New Roman to the careful naivety of Comic Sans, type design informs more than we often acknowledge. In this sense, by bringing Celtic calligraphy into the crises of the 21st century, Ogma is a call to action.

(Written by Lila Boschet)

FO_Portfolio_04

Data sandwich

Design/Researcher: Public Map Platform

Funding stream: Green transition ecosystem

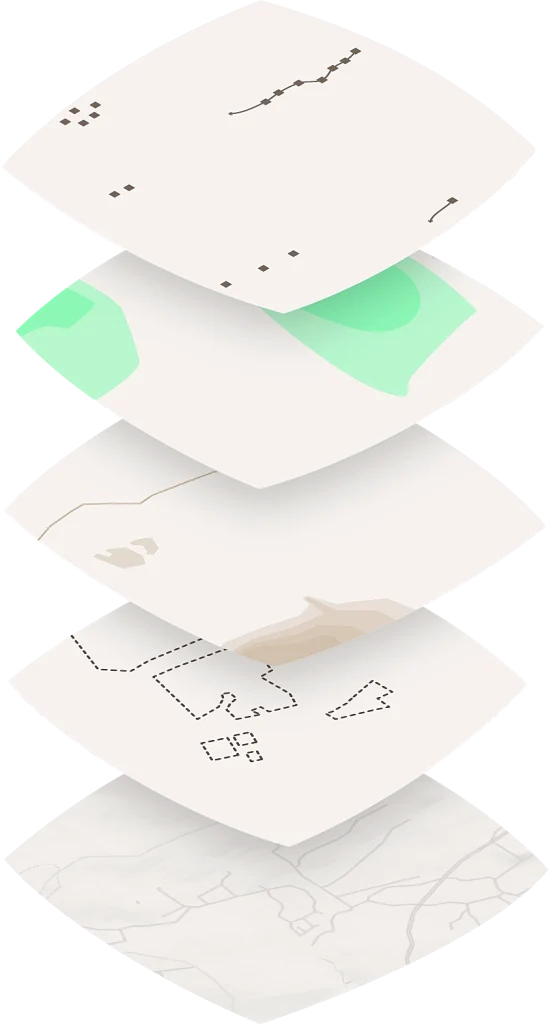

A river, a forest and your street are accounted for in the maps we use, but what about a song, poem or hyperlocal air quality data? Urban planners today use maps created with GIS (Geographical Information Science) software to think about the future of a place through available geospatial data. Although these maps amass vast amounts of quantitative data to help inform future decisions about where we live, they miss out important markers of a place like the wellbeing of a community, their quality of life or their culture. What if it were possible to incorporate the lived experience of people and living things into these decisions?

The vision of the Public Map Platform (PMP), a Future Observatory Green Transition Ecosystem project, is to change the way that planning happens in local authorities across the UK by involving communities in the mapping of their region. As project lead Prof. Flora Samuel noted “typically only 1% of the community will have any say on planning issues in their area because the mechanisms are difficult to engage with and very boring in their current state.” Beginning on the Isle of Anglesey (Ynys Môn), an island sitting off the North West coast of Wales, Samuels and her team will focus on collecting environmental, social and cultural data with local children, young people and their families.

This qualitative data might include recorded sounds, drawings, smells encountered on climate walks, visual records of seasonal blooms and local oral traditions that will mix with more orthodox data (temperature readings and population demographics) to create a layered “data sandwich” of Anglesey. While the project is just beginning, the layers of data gathered over the next months will result in an exemplar public map, to be designed so people can make sense of the data about their region and might further involve themselves in local planning decisions. What’s more, the PMP will allow nuanced understandings of a place to rise to the surface, such that the scent of winter heliotrope, a 17th century musical score and local weather conditions become markers on the map.

(Written by Jennifer Cunningham)

FO_Porfolio_05

Coastal waste brick

Design/Research: SERATECH Cement, Carmody Groarke Architects, Local Works Studio and AKT II Engineers

Funding stream: Design Exchange Partnership

Look around, what colour are the brick buildings in your area? In the UK, if rows of yellow-tinted townhouses dominate the view, that’s down to the London stock brick which gets its distinct colour from chalk in the clay. Or are the buildings rather dark, ashen even? It’s likely the site you are stood used to be a mining hub; the bricks bearing the trace of industrial activity. Bricks and building materials spoke volumes about the bioregions they came from and a Design Exchange Partnership research team are looking to revitalise this practice, albeit with a new perspective.

With prototypes developed in East Sussex, and building on previous experiments in the Belgian city of Gent, the team – comprising Carmody Groarke Architects, Local Works Studio, SERATECH Cement and AKT II Engineers – are working to produce bricks that require no digging; turning construction sites into quarries instead. ‘We used construction waste aggregate sourced from as close to the coastline as possible’ explains Sian Ricketts. ‘It’s a mixed aggregate of concrete, brick, tarmac, seashell and we introduced a seaweed starch into some of the bricks’. The collecting and repurposing of construction waste, as well as seaside detritus, breathes new life into materials that would otherwise go to landfill. More than this, it signals that valuable resources do not only come from below the earth’s surface; they can also be found in your neighbourhood.

Mining the city instead of mining the earth for materials will inevitably colour the built environment with new hues. Years down the line, as you stroll down the shores of East Sussex, take stock of the buildings lining the coast. Notice how the trademark seaside arcades have been built with shell–bespeckled bricks, showing the traces of the stony beach and neighbourhoods gone by contained within the fabric of the buildings.

(Written by Lila Boschet)