The Real Housing Crisis

The ‘abundance agenda’ shouts ‘build, baby, build’, but a country like the UK has enough vacant dwellings to solve its housing crisis – and no carbon budget for a construction frenzy. Rather than simply cutting red tape, we must reimagine what housing is

As trust in government continues to wane across much of the Global North, and with populist leaders revelling in the void, centrist politicians and policymakers are desperately seeking new ideas that might ‘cut through’. The latest hope is in the loose concept of ‘abundance’, with The Economist newspaper calling for politicians to be ‘abundance-pilled … making supply inputs, such as energy, housing, transport and skilled workers, plentiful and cheap’. 1 ‘America’s Democrats Should Embrace “Abundance Liberalism”’, The Economist, 18 March 20205, Source. This ‘abundance agenda’, largely conjured up by journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in their book Abundance (2025), could be summarised simply as ‘making building great again’. Although written almost exclusively from an American perspective, it is impacting policy wonks in the UK, Australia, Europe and beyond, particularly when applied to the apparent ‘housing crisis’ in all these countries. That ‘supply inputs’ rhetoric translates simply to building more houses, no matter the cost. Increasing supply in this way would apparently require a disarming of what Klein and Thompson call government’s ‘arsenal of regulation’.

So, the answer to a housing crisis seems clear: build more houses, then we can all have one. The problem is that, while we do face environmental and inequality crises, there is, in fact, no housing crisis. Or at least, not that one. What if we already had an abundance of housing space in all the countries that the Abundance agenda is aimed at? What if simply making more houses, in a ‘business-as-usual’ way, would not make housing more affordable by any meaningful measure? And given that the built environment sector is our most extractive, what would be the planetary impact of such a careless ‘build baby build’ strategy?

While it’s easy to agree with the starting points of Abundance – housing is a human right, 2 Mariana Mazzucato and Leilani Farha, ‘The Right to Housing: A Mission-Oriented and Human Rights-Based Approach’, Council on Urban Initiatives, 2023, Source. and only government can address grand challenges – their actual strategy turns out to be pouring more fuel into existing engines. ‘Build baby build’ is policymaking as meme, and we are still left facing twenty-first–century challenges with nineteenth–century logics, relegating the world around us to mere natural resources with which to build. Indeed, without changing the ‘system settings’ that direct what housing is, we will simply blow our entire national carbon budgets on new homes while having minimal impact on affordability. Growth has a direction as well as a rate. 3 Mariana Mazzucato, ‘Governing the Economics of the Common Good: From Correcting Market Failures to Shaping Collective Goals’, Journal of Economic Policy Reform 27, no. 1 (2024), Source. Innovation has a direction. Housing has a direction. Right now, our energies must be focused on directing radically different outcomes, not simply more of the same. Sadly, Abundance offers little in terms of the rich diversity of possible futures for housing, energy, mobility, materiality and biodiversity that we will need to imagine and construct the future: in some cases, by building less not more, and in others by completely rethinking what we are building.

If the goal is affordable housing within planetary boundaries, as it must be, then our finite ‘budget’ for emissions and resources should focus almost exclusively on diverse, careful forms of new-build or retrofitted not-for-profit housing. We will need to throw our full capabilities at this – public and private innovation, state capacity and community participation, material technologies and practices – but doing so would produce forms of true abundance beyond the current policy settings and public discourse.

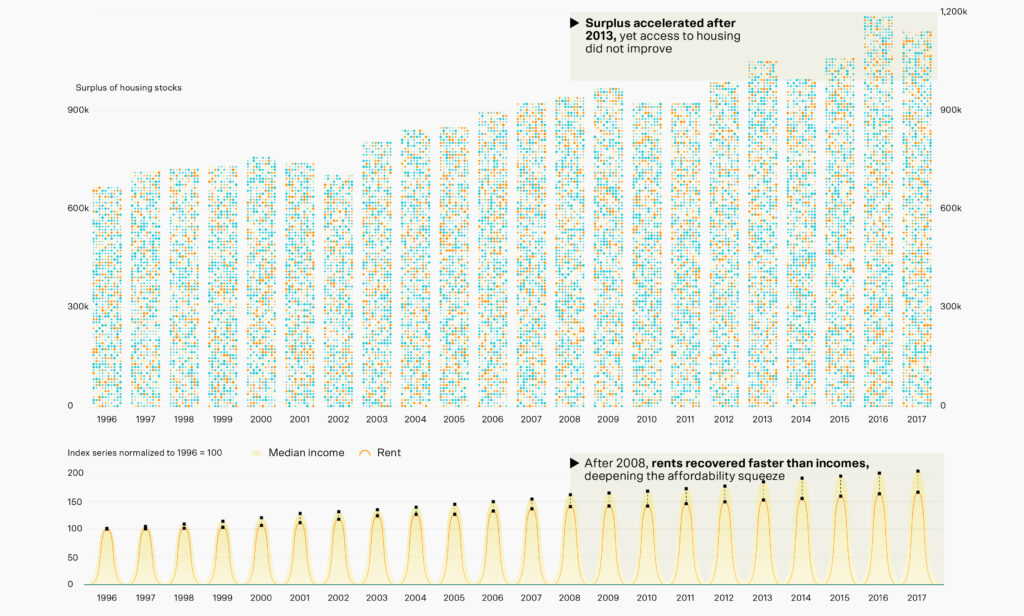

Dwellings in Excess of Households in England

In 1996, England had 660,000 more dwellings than households. Fig. 01 shows how this surplus has grown, even as rent prices have consistently outpaced household earnings

An Abundance of Emissions

Without such a reframing of the challenge of housing, the abundance agenda’s ‘build fast and break things’ approach will, above all, produce emissions. UK-based research finds that if the national targets of 300,000 new homes per year were constructed business-as-usual, England’s housing would consume the country’s entire cumulative carbon budget under the Paris Agreement. 4 Sophus O.S.E. zu Erdgasen, et al., ‘A Home for All Within Planetary Boundaries: Pathways for Meeting England’s Housing Needs Without Transgressing National Climate and Biodiversity Goals’, Ecological Economics 201, no. 107562 (November 2022), Source. Similarly, the Australian Reduction Roadmap project finds that the national targets of 200,000 new homes per year would consume around twice Australia’s total emissions budget. 5 See the Australian Reduction Roadmap: Source. To stay within Australia’s fair share of ‘planetary boundaries’ would require a 98 per cent drop of emissions per square metre of typical new housing, if current practices continue, and within just a few years. Research in Germany confirms that these patterns apply there too, noting that, even optimistically, ‘technology improvements are not sufficient to reach climate targets’, reinforcing the ‘need for housing policies that go beyond simply increasing the supply’. 6 Jakob Napiontek et al., ‘Live (a) Little: GHG Emissions from Residential Building Materials for all 400 Counties and Cities of Germany until 2050’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling 215, no. 108117 (April 2025), Source. From a climate perspective, new housing supply should be a question rather than the only possible answer.

The emissions from housing are made worse by the particular dynamics of the sector, which cause housing space to be over-produced and consume excess land and resources. But Klein and Thompson get housing wrong from the start: ‘Housing follows the laws of supply and demand. When supply is thick and demand is light, prices fall.’

It is not that simple. As economist Josh Ryan-Collins describes, housing supply has minimal impact on affordability in financialised markets where prices are geared not to fall: ‘the fundamental driver of high house prices in advanced economies comes from excessive speculative demand, not a lack of supply’. 7 Josh Ryan-Collins, Why Can’t You Afford a Home? (The Future of Capitalism) (Cambridge: Polity, 2018), 95. This is the ‘housing–finance feedback cycle’. Prices are determined by mortgage credit availability, fiscal incentives, construction dynamics, land value and other factors sitting deep in the system settings.

In the USA, dwellings per 1000 inhabitants stands at 434, squarely mid-OECD pack, 8 See ‘HM1.1. Housing Stock and Construction’, OECD, Source. and that number has been sharply rising for the last decade. 9 Alex Fitzpatrick, ‘Housing is Outpacing Population Growth, but There’s a Catch’, Axios, 9 October 2025, Source. The issue is in another OECD list: the US ranks second to last for affordable housing. 10 See the OECD Affordable Housing Database: Source. In the UK, data shows a surplus of dwellings relative to households, doubling from 1996 to 2019 – including London, 11 Nick Bano, Against Landlords: How to Solve the Housing Crisis (London: Verso, 2024). which has a higher surplus than the rest of the country. Again, the number of new households has been consistently outstripped by additions to the housing stock. Similarly, from 2001 to 2021 Australia’s population increased by 34 per cent yet dwellings increased 39 per cent. 12 Matt Grudnoff, ‘Is Population Growth Driving the Housing Crisis? Here’s the Reality’, The New Daily, 29 August 2025, Source.

However, this surplus of housing does not necessarily produce affordability. In these markets, a gilded cage of tax advantages protects generational wealth in private housing, while homes are not being released back into circulation. Many of the new dwellings remain investment vehicles, as second or third homes and rental properties, a system setting that few, if any, politicians want to touch. As a result, the UK now has over 2.5 million landlords. Lawyer Nick Bano has observed that this is twice the number of NHS employees, four times the number of teachers and double the number of coal miners at the industry’s peak. As he puts it in his book Against Landlords: How to Solve the Housing Crisis, landlordism is the ‘closest thing that Britain has to a national industry’.

An Abundance of Empty Bedrooms

This transformation of the idea of ‘home’ into investment vehicle has overproduced housing space. Australia’s 2021 census revealed 13 million unused bedrooms, including 1.2 million properties with three or more spare bedrooms. 26 See the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute analysis: Source. There are hundreds of thousands of completely empty houses. Australia’s overwhelmingly private housing sector tends to produce both ‘lowest common denominator’ homogeneity 27 Rachel Gallagher et al., ‘Building to the Lowest Common Denominator: How Uncertainty of Approval, Cost and Delays Discourage Housing Diversity in Infill Development Projects’, Cities 165, no. 106095 (October 2025), Source. and the largest new houses in the world 28 Kate Wingrove and Emma Heffernan, ‘Australian Homes are Getting Bigger and Bigger, and it’s Wiping out Gains in Energy Efficiency’, The Conversation, 6 March 2024, Source. – at 240m2, double the average of 120m2 in 1969 29 André Stephan and Robert Crawford, ‘Size Does Matter: Australia’s Addiction to Big Houses is Blowing the Energy Budget’, The Conversation, 13 December 2016, Source. – even though household size has been dropping – from 3.3 people per household in 1969 to 2.6 today. 30 See ‘Population, Households and Families’ published by Australian Institute of Family Studies: Source.

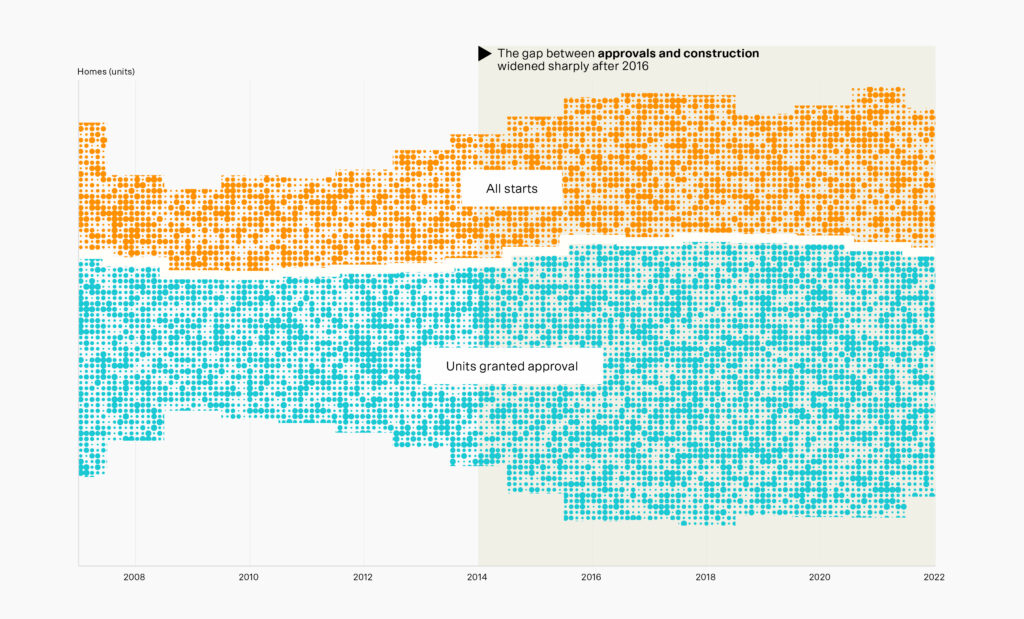

Bano reports that ‘In 2021 about 70 per cent of housing in England and Wales was under-occupied, whereas less than 5 per cent was overcrowded.’ Yet the abundance agenda remains fixated on the ‘burdensome’ planning processes that are preventing further new housing. This doesn’t stack up: around 80–90 per cent of UK planning applications are approved, 31 See Local Government Analysis: Source. and Australia has no huge backlog of applications either. Across Sydney, 75,000 planning-approved homes haven’t started construction. 32 Max Maddison, ‘Over 75,000 Approved Homes Yet to Commence Construction’, Sydney Morning Herald, 2025, Source. Economic geographer Brett Christophers has been tracking ‘land banking’ by volume builders – in the UK, the number of planning-approved but unbuilt development applications increased from 475,000 in 2015 33 Brett Christophers, The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain (London: Verso Books, 2018). to almost 1m plots by 2022, enough to keep building until 2040. 34 Steve Howell, ‘Labour Must Urgently Tackle Land Banking to Have Any Hope of Solving UK’s Housing Crisis’, Big Issue, 18 December 2023, Source.

While planning systems and building codes could – and should – be significantly refined, these signals are hardly evidence of a laggard bureaucracy. If the primary engine for housing delivery remains private developers and financiers, their construction and sale will be timed to produce maximum profit margins, linked to house price and rental yield cycles rather than housing demand. Such developers typically need house prices to go up, not down, to deliver housing.

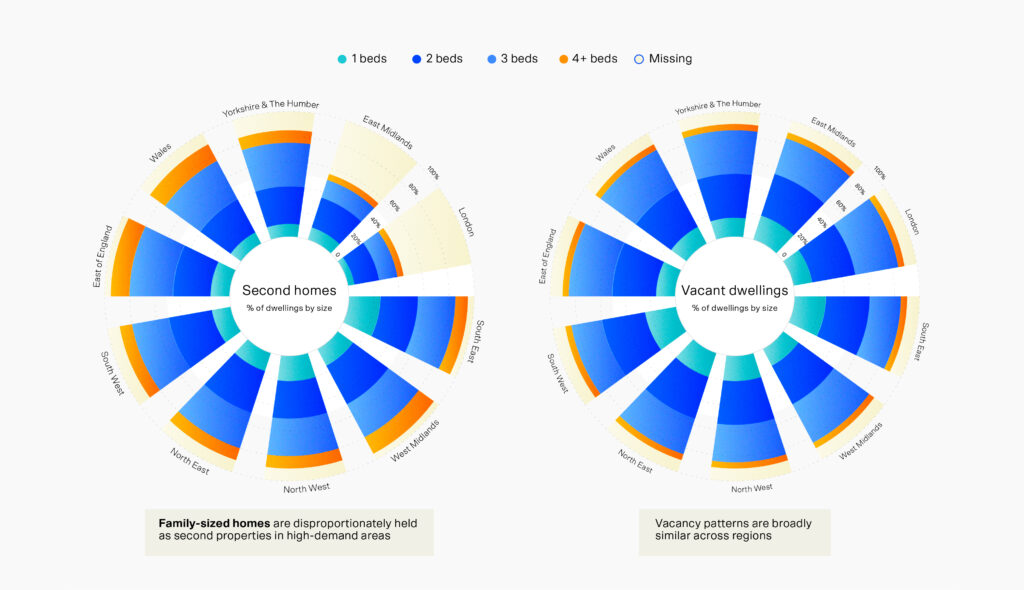

In 2021, there were 1,627,550 unoccupied dwellings in England and Wales combined

Fig. 02 compares sizes (by bedroom) of second and ‘truly vacant’ dwellings. Across England and Wales, 2–3 bedroom dwellings dominate the second-home and vacant stock

An Abundance of Inequality

Even significantly increasing supply would do little for affordability. For England, research shows a 1 per cent increase in housing stock delivers only a 1–2 per cent price reduction. As the LSE’s Ian Mulheirn notes, even a ‘full steam ahead’ nation-building effort to construct 300,000 houses every year for 20 years – a volume last achieved for a few years in the 1960s by a hugely capable state-led operation – would only cut house prices in England by around 10 per cent. 13 Ian Mulheirn, ‘Why Building 300,000 Houses Per Year Won’t Solve the Housing Crisis – and What Will’, LSE BPP, 28 August 2019, Source. English house prices rose 181 per cent from 2000 to 2020, effortlessly outpacing that saving. Unaffordable housing, Mulheirn concludes, is little to do with the blunt toolkit of supply-side construction, but is instead driven by slow wage growth, diminished public housing stock specifically and financial incentives that prioritise the production of landlords over homes. The patterns are even more extreme in Australia, with salaries showing no sign of catching up with a house price growth of 100 per cent over the last decade, and 400 per cent for the last 25 years.

The simple volume of houses in these markets makes little difference. Spain, near the top of the OECD list, with a handsome 564 dwellings per 1000 people, also faces a housing affordability crisis, as do Italy and Portugal. The clue is that these countries have relatively small proportions of public housing. In places with more benign markets, such as the Nordics, Switzerland and Germany, more diverse housing sectors include significant proportions of public or community-owned housing. The proportion of public housing in Australia and the United States is among the smallest in the OECD – at around 3 per cent, it is almost an order of magnitude below that of the Netherlands.

Positioning homes as investments produces effects outside of housing. As the ‘housing-finance feedback cycle’ now dominates contemporary economies, the engineered returns on property attract banks away from investing in businesses or other forms of economic activity. This numbs the ‘real economy’, causing wage stagnation and further increasing mortgage debt.

Without changing system settings, increasing supply leaves housing further out of reach, even after disruption and extraction of attempting to construct hundreds of thousands of homes annually, for decades. Affordability concerns the direction of housing – tenure type, ownership models, spatial form, build quality, climate resilience – rather than mere volume. Housing is affordable if it is made affordable. 14 Dan Hill and Mariana Mazzucato, ‘Modern Housing: An Environmental Common Good’, Council on Urban Initiatives (2024), Source.

Supply does matter to some degree, clearly, not least as much existing housing will need retrofitting or replacing (the Buildings Performance Institute Europe suggests that 97 per cent of buildings in the EU require renovation to improve energy performance). 15 See the 2017 publication: Source. But any actual shortage is largely in public and community housing, the only models that remove housing from financialisation’s grip. By bringing together housing and climate policies, we might focus our remaining emissions budget solely on this gap in sustainable public and community-led housing, creating innovation vehicles that legitimately tilt the playing field towards the common good, and redesign rules and practices in ways that private development cannot. This is just as the public sector did in previous eras – whether the 1960s Swedish Million Programme, Singapore’s Housing Development Board, the UK’s postwar rebuild, Vienna’s century-long investments in exemplary housing, as well as more recent revivals of public housing in London and municipally supported cooperative housing in Barcelona and Zurich. The answer is not simply ‘let the private sector rip’, but genuinely deploying all sectors. What’s stopping us?

A Growing Gap Between Approvals and Construction

Fig. 03 shows how planning permissions climbed sharply after 2016 while new housing starts lagged, pointing to delivery failures beyond the planning system

Most of us in the Global North – politicians, policymakers, practitioners, educators, citizens – simply do not think about these diverse models. Instead, we have been living through a historically unusual moment, in which housing has been quite deliberately framed as asset class rather than home. That has become the orthodoxy. In 1932, Keynes wrote in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, ‘The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones.’

Yet design’s capability to reframe the familiar is useful here. A decade before Keynes, Le Corbusier stated in Vers un architecture (Toward an Architecture) that ‘The problem of the house is a problem of the epoch … Architecture has for its first duty, in this period of renewal, that of bringing about a revision of values, a revision of the constituent elements of the house.’

Every time we make a house, we are making decisions, implicitly or explicitly, about climate, about health, about social justice. As a result, we can ‘solve for’ all these things at the same time, something Klein and Thompson think is impossibly complex. To do so requires us to foreground our values in design and policy – to recognise that housing embodies what we stand for as a society. If we make high–quality public housing – carefully designed, constructed and maintained – it says something about what we believe in. If we don’t, it speaks equally loudly as to our values.

If housing is constructed of values, as much as timber and stone, what could be on the drawing board? What ‘revision of values’ might see us move away from the reductive idea of home as a mere financial instrument?

An Abundance of Care

Apparently inspired by the Abundance agenda – Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers has called the book ‘a ripper’ (Australian for ‘very good’) – the outcome of the Australian government’s recent Economic Reform Week was a proposed freezing of revisions to the planned National Construction Code until 2029, locking in extractive design and construction. 16 Patrick Commins, ‘Abundance: The US Book is a Sensation Among Our Progressive MPs. But Can It Spur Action in Canberra?’, The Guardian, 12 July 2025, Source; David Spears, ‘Albanese Government to Freeze Construction Code until 2029, Fast-track Housing Approvals’, ABC News, 23 August 2025, Source. But what would it take to ensure housing as a human right and an environmental common good? What would changing system settings – rather than locking them down – actually look like? And what new direction might housing take, rather than simply more of the same?

In Australia, the Reduction Roadmap is building a movement to bring that ‘frozen’ national construction code back into play, with a specific goal of introducing an embodied emissions limit for housing, aligned with the Paris Agreement. It also outlines an array of actions that would diversify and enrich the approach to housing. These include a shift to mass retrofit, a reorientation of architectural practice around existing built fabric and materials, a ‘less but better’ approach to sufficient housing space, system innovation for flourishing supply chains of circular biogenic materials, an industrial policy for fabrication innovation powered by renewable energy, fiscal reform to remove financialisation incentives, and inventive public procurement and legislation to transform the quality and volume of public and shared ownership housing.

The Australian roadmap is a counterpoint to the successful Danish precedent, 17 See the Danish Reduction Road Map: Source. which introduced the world’s first embodied emissions limit for housing in 2023, and variations on all these systemic changes are coming into play elsewhere. Exploring similar themes for the UK, the Homes that Don’t Cost the Earth initiative brings together Arup, Dark Matter Labs, Rising Tide and UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. 18 See ‘Homes that Don’t Cost the Earth’: Source. The City of London is now prioritising retrofit-first in its planning regulations, 19 Will Hurst, ‘City of London’s “Retrofit First” Policy to Come into Force’, The Architect’s Newspaper, 22 January 2025, Source. while the UK has introduced requirements for ‘biodiversity net gain’ 20 See government guidance: Source. in new developments and announced a £39 billion public investment in social and affordable housing over the next decade. 21 Ministry of Housing, ‘Over 500,000 Homes to be Built Through New National Housing Bank’, press release: Source. France requires that all new public buildings should be 50 per cent timber or similar biomaterials. 22 Sydney Franklin, ‘France Mandates Public Buildings Be Built with At Least 50 Percent Timber’, The Architect’s Newspaper, 11 February 2020, Source. Numerous governments around the world use forms of rent control to tilt markets towards affordability. A 2011 referendum in Zurich resulted in a commitment that cooperative housing increase to 33 per cent of all residential units by 2050, precisely to ensure affordability. 23 Alexis Kalagas, ‘Co-op City experiments with non-profit housing in Zürich’, Assemble Papers, 25 January 2018, Source.

Each measure is typical of what the abundance agenda finds ‘burdensome’. Each stimulates innovation in design, construction and public policy, and thus works as industrial strategy as well as climate action. Practices are rising to the challenge accordingly. For example, the UK-based architecture office Material Cultures has documented the rich palettes of regenerative biomaterials we can now draw from to make housing. 24 Material Cultures and Amica Dall, Material Cultures: Material Reform Building for a Post-Carbon Future (London: Mack Books, 2025). This is one of the more thrilling developments ahead, asking us to shift practices, places and capital around the natural abundance of new and old material supply chains.

An Abundance of Possibility

Policymaking is harder than simply stepping on the gas to see what happens. Noting that private venture capital can typically write-off 80 per cent of its gambles, it’s clear that the public sector typically requires a more sophisticated and careful form of innovation. It increasingly needs highly skilled, well-resourced staff, cultivating so-called dynamic capabilities 25 Rainer Kattel et al, ‘Assessing Dynamic Capabilities in City Governments: Creating a Public Sector Capabilities Index’, UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, IIPP Policy Report 2025/05, (2025), Source. , not least as it faces a situation in which good policy apparently equals bad politics. Klein and Thompson seem to recognise how difficult this bind is for public practice and often write powerfully about the value of state capacity. What’s mystifying is that their proposed remedies undercut any meaningful change in circumstances for the public sector. We will only make great strides across unnecessarily restrictive bureaucracy by activating our imagination about what bureaucracy might be.

Rather than simply wishing regulation away, what about reinventing it? What are the re-tooled planning and construction codes that we need, recognising that they must be more ambitious, not less, about systemic change? This dark matter is the code that writes the city. Like computer code, it can be one of our most powerful materials, allowing us to hold systems accountable in order to reimagine and reshape the structural forces that produce one set of outcomes rather than another. A building code makes building happen, rather than preventing it. A good one ensures that what is built is healthy, sustainable and equitable. We need more designers and builders of public code.

Such integrated policy goals are indeed slightly harder than just ‘build more’. In democratic countries, they ask our politics to take on these challenges, ‘not because they are easy but because they are hard’. They ask designers and builders to raise their game. They ask policymakers to recalibrate systems such that good policy equals good politics. All this requires us to rebuild and reinvigorate state capacity, devising inventive practices that support the delivery of diverse housing models that touch the earth lightly and serve the common good, rather than merely accelerating private extraction. That would be true abundance.