Off The Map

Reflecting on the friction between hard political boundaries and the blurry edges of bioregions

Campan is a village of 1288 people, located in an eponymous valley of the Pyrenees, a 500-kilometre mountain range straddling the border between France and Spain. Archaeology and a variety of historical records tell us there has been a community here for several millennia. This valley sits at the limit of the Pyrenees’ Axial Zone, a geological area dating back to the beginning of the Earth more than 4 billion years ago, where all the range’s highest peaks are located. It offers a variety of terrain: from granitic rocks and mediocre pasturage to Devonian limestone and lush meadows, perfect for grazing. Glaciers and rivers running above and below ground have profoundly changed the relief of the valley. Some parts, smoothed out by time and water, have become weak gradients, almost horizontal, with little natural obstacles. This absence of an obvious ‘natural’ border between Campan and the neighbouring valley of Aure has been an ancient source of disputes to control the summer pastures. Local lore has it that the two valleys once organised a duel to death between two of their shepherds, each representing a village, to decide the territory they would control once and for all. But conflicts continued to break out sporadically, at least until the 17th century. Campan is also a ‘border community’, close to present-day Spain and other ancient tiny kingdoms of which only the Principality of Andorra, founded in 1278, remains. The term is archaic now, but this kind of territory was called a ‘march’ or a ‘mark’, meaning a borderland characterised by some form of hybridity – between languages, customs, legal systems and so on. A buffer zone, not to be understood as a no-mans-land, but instead as a space of intense communication and exchange.

In this essay, I want to explore the idea of bioregionalism – that is to say identifying spatial entities where nature and humankind constitute an identifiable ‘community’ – by critiquing some of its fundamental contradictions. In doing so, I am not aiming to discard the concept of bioregionalism, quite the opposite. I want to elevate the tensions encapsulated in this idea in order to explore omnipresent strains in design thinking – between cartography and boundary-setting, between knowledge and appropriation, control and laissez-faire. I will specifically question three notions inherent to bioregionalism: natural borders (as opposed to political ones), scales and representations. Before travelling on to the Alps, the San Diego-Tijuana border and outer space by way of Kenya, let us return to the modest valley of Campan, latitude 43 degrees north, longitude 12 degrees east, where our journey begins.

In 1954, aged 53, French philosopher Henri Lefebvre presented his rural sociology doctoral thesis on the community of the Campan valley. His work set out to question ‘what have been the qualities of this human group that managed to take such advantage of a favourable soil; to seek the historical and sociological conditions in which these qualities appeared’. 1 Henri Lefebvre, ‘The Valley of Campan, a Study on Rural Sociology’, in Migrant Journal No. 1: Across Country, trans. Justinien Tribillon. London: Migrant Journal Press, 2016, 115. We know Lefebvre today for his study of cities: for concepts such as ‘planetary urbanism’ or the ‘right to the city’. But he first started to question space as a sociopolitical entity by focusing on the countryside of the Pyrenees. Through the prism of Campan, Lefebvre understood that space is not a given and is neither objective nor natural: it is a product of our society. From this initial take on rural communities, the philosopher eventually developed a critique of space at a global scale that would shake our apprehension of the world around us to the core. 2 For an overlook of Lefebvre’s work, see Andy Merrifield, Henri Lefebvre: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2006. Among those preconceptions that Lefebvre’s critique of space enables us to question is the idea of a ‘natural border’:

The notion of ‘natural border’ has in that small story the same as in the great history: somewhat justified, somewhat arbitrary, with the meaning to be found in a specific economic structure and policy. 3 Lefebvre, ‘The Valley of Campan, a Study on Rural Sociology’, 120.

Natural border is the idea that a place and its community are bounded by elements of landscape that make them ‘natural’, that is to say evident, unchallengeable or logical. A mountain, a river, a sea or a forest are elements that could constitute natural borders. The idea is enticing: to reconnect with the Earth, we acknowledge the limits nature has set for us – humans – and also for animals and plants.

Bioregionalism offers us two divergent, if not completely opposed paths to reassess the ideas of natural/political borders. The first path uses natural elements to transcend borders, creating new imaginaries and, eventually, new civic institutions to oppose nationalism and its urge to define who is ‘in’ and who is ‘out’. The second, by proposing to reassess spatial entities based on ‘natural’ traits instead of political boundaries is, intrinsically, promoting the idea of natural borders, suggesting that nature – a landscape – can constitute an objective, unmediated set of information. In doing so, it overlooks the necessary political aspect of the ‘natural’.

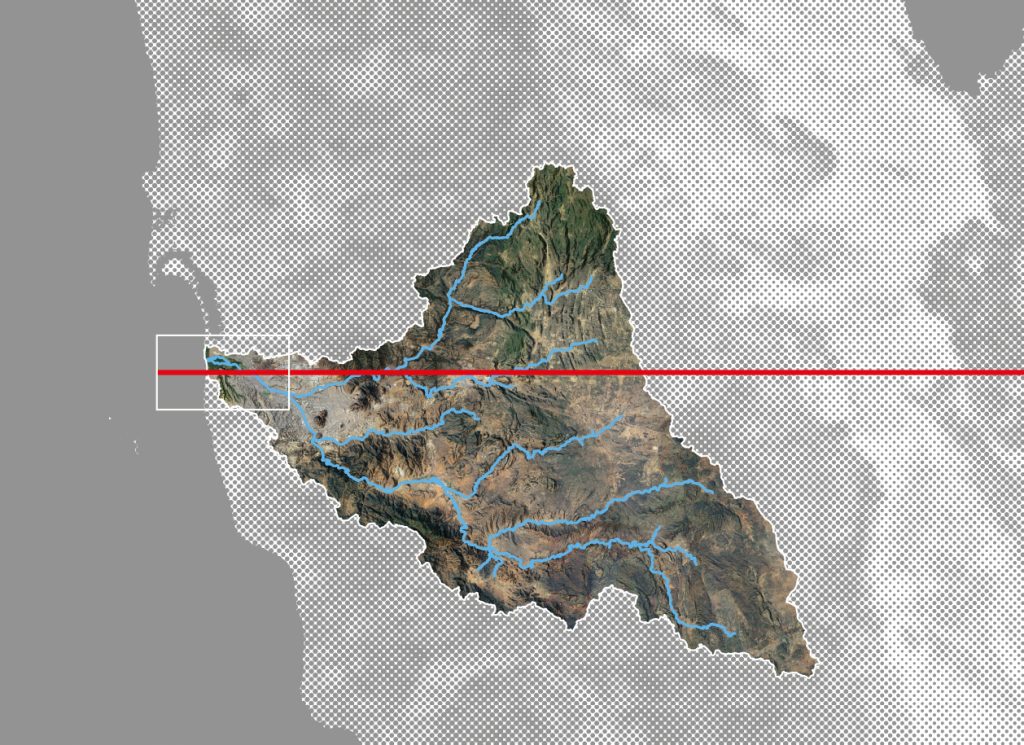

Based in San Diego, California, architecture and research practice Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman have focused on the border between Mexico and the United States for more than a decade, specifically the adjacent border towns of Tijuana and San Diego. Their research and programming spans cultural experiments to initiating transnational coalitions of universities, grassroots activists and public-sector agencies, but also teaching and art installations, on-site and abroad. In their project MEXUS for instance, which challenges the representation of the border by way of maps and art installation, they have found inspiration in the landscape, specifically in the watershed system that spans both countries, to act as ‘a powerful imaginary for activating more elastic civic thinking’. 4 Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman, ‘The UCSD Community Stations: A Bioregional Infrastructure for Ecosocial Justice’, Field Winter 2023, no. 26 (February 2023).

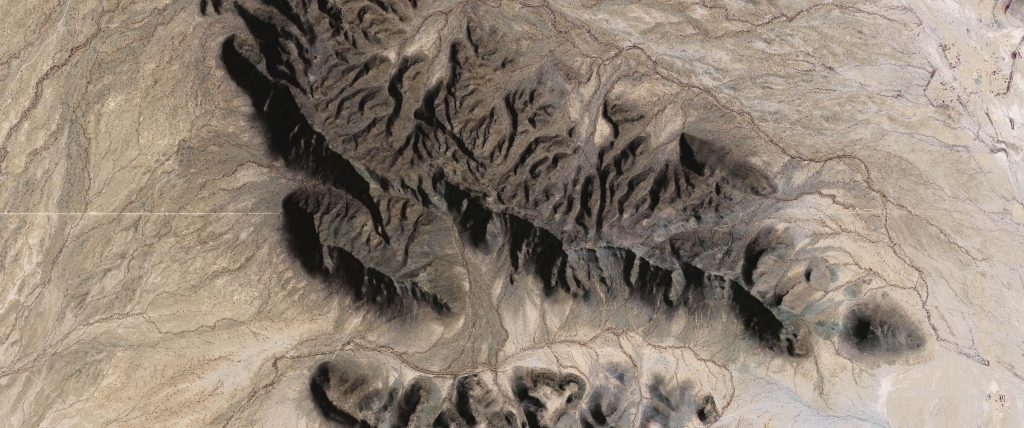

This challenge to ‘racist political narratives’ takes inspiration from the topography of the Tijuana canyons and the environmental coastal reserve of San Diego now crisscrossed with security infrastructure. I invite you, reader, to enter the coordinates 32°32’06N 117°05’51W in your favourite map software to discover a bird’s-eye-view perspective on the Los Laureles informal settlement, the site of one of Estudio Cruz + Forman’s interventions. Now consider the militarised border line between the two countries clashing with the topography of its landscape, obvious even to the untrained eye. Cruz and Forman’s project resolutely plays with a variety of spatial scales, from the hyperlocal to the continental and even the global. MEXUS has also developed into a continental cartographic exercise to challenge nationalist imaginaries, where they have represented the watershed systems spanning the political border between the USA and Mexico, without featuring the line of demarcation itself. In doing so:

It dissolves the border into a bioregion whose shape is defined by the eight binational watershed systems bisected by the international border. MEXUS also exposes other systems and flows across this bioregional territory: tribal nations; protected lands; croplands; urban crossings, many more informal ones, 15 million people, and more. Ultimately MEXUS counters America’s wall-building fantasies with more expansive imaginaries of belonging and cooperation beyond the nation-state. 5 Cruz and Forman, ‘Unwalling Citizenship’, e-flux Architecture, 2020. Source

But the idea of ‘nature’ in connection to a territory and a community also has a dark history. If Cruz and Forman’s endeavour is dedicated to challenging the racist narratives that have turned borders into sites of violence, fear and death, the idea of bioregionalism and ‘natural’ borders can be pushed precisely to enforce such narratives. If we scale up the conflicts between small valleys in the 16th century to that of modern nation-states in the 19th and 20th centuries, the idea of natural borders can become a dangerous concept, instrumentalised by humankind’s worst ideologies.

The concept of – literally ‘living space’ but that also translates as ‘habitat’ or ‘biotope’ – for instance, is anchored in geography and biology and became the justification for Nazi Germany’s expansionist wars and genocidal programmes. Developed in association with the slogan Blut und Boden – the idea that a racial identity (Blut, blood) is linked to territory (Boden, soil) – Lebensraum compared society to an organism whose natural territorial limits should expand beyond its current political borders to ensure its survival. Mussolini’s Italy, meanwhile, had Mare Nostrum, a Latin expression to describe the ‘evidence’ that the countries and peoples around the Mediterranean basin were essentially theirs to claim and conquer. Arguably, all conflicts of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that involved nation-states – including the conflicts currently raging in Ukraine and in Israel/Palestine – can be boiled down to the idea that a national community’s ‘natural’ borders should expand at the detriment of their neighbours’ territories and that war, therefore, was justified, if not natural. Yet more than expanding beyond the political or ‘natural’ borders of a nation state, I argue that all apprehension of ‘nature’ by humankind, especially any effort to set boundaries, is intrinsically political.

Scale is key. The jump I have made between a tiny valley in the Pyrenees and countries with a population of millions might seem preposterous but a bioregionalist approach to space brings to the fore the idea of scale. For some, a bioregion should be defined by Indigenous knowledge, microclimates and ‘natural’ boundaries. Some kind of community-led definition from the bottom up. For others, the concept of bioregion becomes a scheme of planetary scale where the world is neatly divided into ‘biogeographic regionalisation of the Earth’s terrestrial biodiversity’. 6 World Wildlife Fund, ‘Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World’, 1 August 2012. Source Once again, there is nothing ‘natural’ or objective in the way we apprehend scale. For most of Europe’s pre-Industrial Age – that is to say, for several millennia – a valley such as Campan constituted a coherent and integrated space, with a specific culture, an identifiable architecture, a specific legal system and local myths passed on from generation to generation. Yet for most of us today, the idea that a valley and its community of a thousand souls constitute a bioregion will seem inadequate. Indeed, our perception of scale has shifted. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century and the Information Age that took shape in the mid-20th century, our reading of landscape has changed. A valley such as Campan hardly constitutes a space large enough to be considered, even by locals, as a bioregion. And so, it is not the set of ‘natural’ information provided by the landscape around us that has changed. Instead, it is our perception of this space.

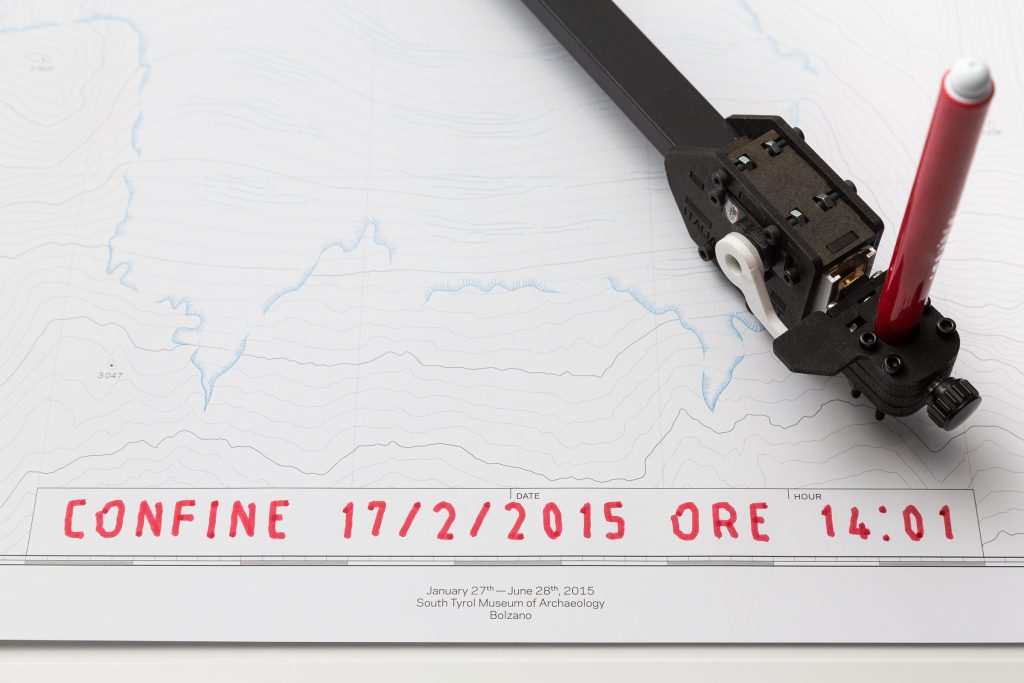

Designers have demonstrated they have the tools to critically challenge the friction encapsulated in bioregionalism, by challenging scales, preconceptions, representations, narratives and ultimately imaginaries. The project Italian Limes by design practice Studio Folder (Marco Ferrari and Elisa Pasqual, joined by Alessandro Busi and Aaron Gillett for this project) offers a playful and yet powerful approach to challenging the idea of natural borders and our perception of a nation’s space. 7 Marco Ferrari, Elisa Pasqual and Andrea Bagnato, A Moving Border: Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change. New York, NY: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2018 The border Italy shares with Austria and Switzerland partially runs over a glacier that has been shifting due to global warming: a 50 per cent decrease since 1850 and a rate of shrinkage that has tripled since the 1970s. In 2006, treaties between Italy and its Alpine neighbours agreed on a new definition of a ‘moving border’, with the Istituto Geografico Militare – the military institution in charge of mapping Italy – organising high-altitude campaigns every two years to map the changing edges of Italy. Studio Folder, by way of GPS probes positioned along the Grafferner Glacier, allow visitors to their installation to draw a ‘live’ map of the Italo-Austrian border by way of a robotic arm. A line that would have potentially changed between a visitor coming in the morning, and one coming in the afternoon of the same day.

As MEXUS and Italian Limes demonstrate, our apprehension of the bioregion is intrinsically connected to the representation of space, specifically cartography. One of the conundrums Italian Limes illustrates by way of design is the tension between a fluctuating border and its analogue, fixed representation by way of a sheet of paper and pen handled by a robot, itself interpreting data sent out by GPS probes. From a design perspective, one of the fascinating challenges set out by the concept of a bioregion is the relationship between cartography, appropriation or even colonisation, and the ambition to create a novel, more respectful relation to local ecologies.

Our obsession with cartography is inherently connected with our desire to control and relates also to our obsession with boundary-making.

Supporters of bioregionalism justly denounce the inept political borders that have been a source of conflicts between nation states, but also a vehicle for the colonisation, exploitation and destruction of peoples as they negate vernacular modes of boundary setting. Think about the imaginary straight lines represented on maps going for thousands of miles between Algeria and Mali, Namibia and Botswana, Canada and the USA. Cartography is the expression of power and knowledge, that are in turn connected to property and oppression. Maps are not objective, but projections of a vision of the world, used by those who produce them. 8 John-Brian Harley, ‘Maps, Knowledge, and Power’, in The Iconography of Landscape : Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments, ed. Denis E. Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, 277–312. As landscape architect and academic Danika Cooper writes in her contribution to Samia Henni’s edited volume Deserts Are Not Empty, in which the contributors critique the perceived ‘emptiness’ of deserts as a heritage of colonialism:

the crafting of landscape images requires deliberate acts of selection by their makers—privileging certain features, view sheds, subjects, and temporal moments, while simultaneously rendering objects invisible. 9 Danika Cooper, ‘Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds’, in Deserts Are Not Empty, ed. Samia Henni. New York, NY: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2022, 80–81.

Our obsession with cartography is inherently connected with our desire to control and relates also to our obsession with boundary-making. If bioregionalism is an attempt, potentially subversive, to reinvent the commonwealth between human and non-human beings and to go past existing political structures of oppression, then we need to ask ourselves: How can we design new spatial representations that do not mimic the pseudo ‘objectivity’ of maps as we know them, but instead make way for new modes and tools of spatial representation?

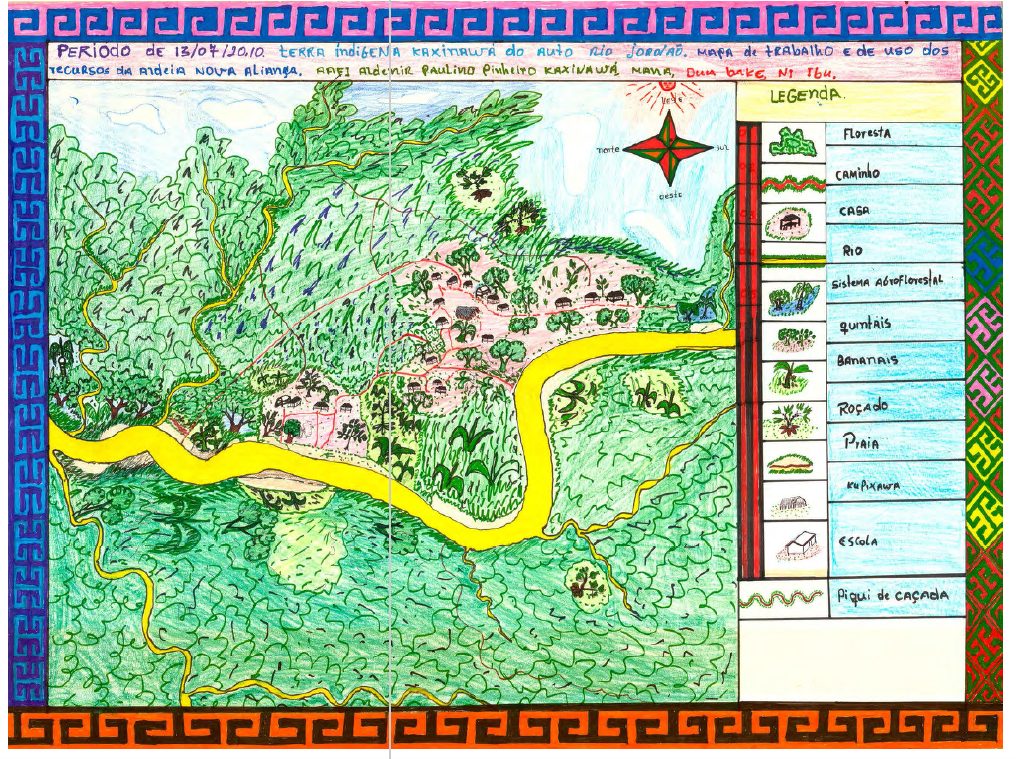

In their Open Access book This is not an Atlas (2018), kollektiv orangotango – a network of activists, critical geographers and artists that challenge the nexus space, power and resistance by way of critical mapping – offers a fascinating selection of ‘counter-cartographies’ from all over the world. In its ethics, methods and aesthetics, the ‘Indigenous Cartography’ that informs the management of the Acre Indigenous Land at the border of Brazil and Peru offers an inspiring way to reflect on turning the relation of power upside down by way of mapping, from ‘tools that were historically used against [Indigenous communities]’ to ‘the production of mental and geo-referenced maps, created through education, [that] incorporates deep knowledge that Indigenous people have about their lands and environment’. 10 kollektiv orangotango+, This Is Not an Atlas. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2018, 111.

Instead of a map designed by a ‘gate-keeper’ – an individual, or an institution that possesses the knowledge and passes it from the top down – the ‘ethnomaps’ are designed through workshops that bring together ‘indigenous representatives to discuss conflicts, problems and advances related to spatial and environmental management’. 11 kollektiv orangotango+, 111. By mixing tools and techniques (including handwriting, GIS softwares and Indigenous abstract representation of spaces), the maps produced are knowledge-sharing communication tools between the various stakeholders, a device to fight for Indigenous political claims, and enable the preservation of vernacular knowledge. In doing so, they constitute a powerful planning tool for the collective management of land and natural resources.

Bioregionalism might have already become what linguist Uwe Pörksen calls a ‘plastic word’, that is to say a word whose meaning has become so malleable that it can fit any circumstance depending on the interlocutors. 12 Uwe Pörksen, Plastic Words: The Tyranny of a Modular Language. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania University Press, 1995. A word whose meaning has been smoothed out by its success. There are two sides to this coin. Obverse: that there is potentially no consensus into what bioregionalism precisely means – words are all about precisely conveying an idea, after all – and that this weakens the concept. Reverse: that the word is so important for us that it necessarily escapes strict definitions to become an evocation, a lead, a tenuous aspiration. Through the examples and thoughts I have offered in this essay, I wanted to analyse some of the tensions that are inherent to bioregionalism in relation to design. Bioregionalism should, arguably, not become another ideology of control, boundary-setting and localism – an excessive devotion to a particular locality, even if that ideology is initially based on a more respectful take on ‘nature’ and local ecologies. But the concept should be a fundamental challenge to our traditional modes of representing and appropriating spaces: a celebration of fuzziness, malleability, hybridity and what we cannot define or even comprehend. In other words, a de-centring of spatial design and the ideologies that stand at its core.