Animal House

A redevelopment proposal for the Mäusebunker, a disused animal testing facility in Berlin, offers a new way of imagining the architecture for multispecies existence

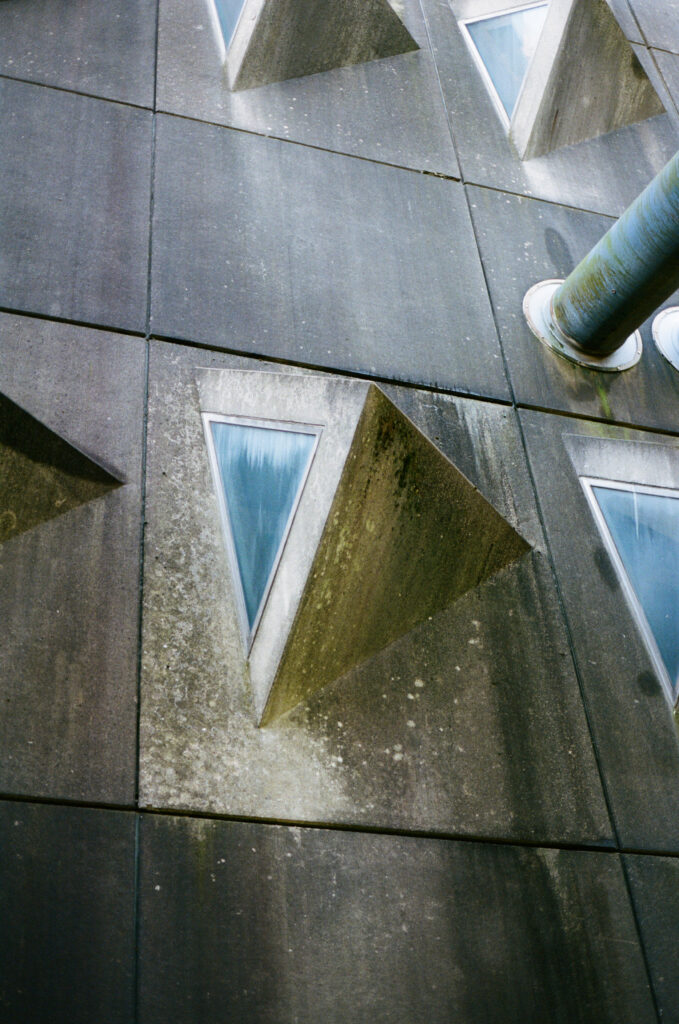

In a quiet suburb of southwest Berlin lies a building that looks like the foreboding lair of a comic book villain. It sits incongruously in its leafy surroundings, hulking and fortress-like in its scale, with an exposed, grey concrete facade, steeply inclined walls, tetrahedral windows that project like spikes and a phalanx of blue steel air intake pipes that protrude from its sides like the guns of a battleship.

This is the former Central Animal Laboratory of the Freie Universität Berlin. Designed by husband-and-wife duo Magdalena and Gerd Hänska, works began in 1971 and it was completed in 1981 following a protracted construction period hampered by spiralling budget issues.

Its bunker-like form was dictated by the grisly requirements of being one of the largest animal testing laboratories in Europe: at any given time, it could house 88,000 animals including 45,000 mice, 20,000 rats and 5,000 hamsters along with frogs, chickens, pigs, sheep and dogs. For security and hygiene purposes its labs were located deep within the building. To ensure sterile conditions much of the structure was effectively sealed off from the outside world with every other floor (totalling some 60 per cent of the building) given over to a complex ventilation and services system. Over time, its closed off appearance and macabre function led to it acquiring the nickname Mäusebunker (Mouse Bunker).

Upon its completion in 1981 the Mäusebunker was instantly controversial, due not only to its being a site of animal testing but also its almost unapologetically sinister appearance. Its opening was picketed by 150 animal cruelty protesters and that same year the building’s lobby was bombed with a Molotov cocktail. 1 This attack led to Germany’s first ever jail sentence for a crime motivated by animal welfare concerns. Fears for their security meant employees often had to enter through a secret tunnel from another campus building across the street.

The building continued to be used as a site of animal testing over the following decades. In 2009, asbestos was discovered throughout much of the structure and research was gradually relocated to other sites managed by its new owner, the Charité university hospital. In 2020, the Mäusebunker was officially decommissioned and, that same year, the Charité announced plans for its demolition.

Despite its controversial history, this demolition notice triggered a campaign to save the building as a site of architectural significance. The ensuing debate around whether or not to save it hinged partly on its formal qualities, and on the carbon saving benefits of preserving such a vast concrete structure. However, an additional social and ecological discourse has also emerged, around how to reckon with the building’s history and what position that should play in its possible future. 2 This has been developed in particular by the series of public ‘Modellverfahren Mäusebunker’ (Mäusebunker Model Process) workshops organised between October 2022 and February 2023 by the Berlin Heritage Authority in partnership with the Charité hospital and the senate department for urban development. In May 2023, the Mäusebunker was officially placed under protection by the Berlin State Monuments Office, thus saving it from demolition. With its immediate future secured, the building now sits in a form of bureaucratic limbo, with planning and debate currently underway around what happens next.

Among the various concepts and proposals developed over the last few years, one of the most widely documented and compelling has come through the Berlin-based architecture practice b+, a collectively run studio founded by Arno Brandlhuber. Their plan centres on converting the building into a site for multispecies cohabitation, offering a major narrative U-turn for a former animal testing laboratory in which a once hermetic and sealed off space is broken open and non-human life is allowed to enter, this time of its own free will.

On a grey Thursday in September, I visit the Mäusebunker to meet with Roberta Jurčić and Jonas Janke, two partners at b+ who have been working on the proposal in dialogue with Berlin’s Heritage Authority since the building was listed in 2023. 3 Prior to this the practice had already been engaging with possible future uses for the site through a master’s studio led by Brandlhuber at ETH Zurich in 2020, which later formed the basis for plans exhibited at Suddenly Wonderful, an exhibition held at the Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art in 2023 that aimed to celebrate and speculate on new futures for iconic 1970s Berlin architecture. The building itself is officially off limits due to health and safety fears around air quality, although several smashed windows hint that people have been finding their own way inside. Following the perimeter of the site we make a slow loop of the building.

What is immediately apparent is that, during the five years in which the building has stood empty, a form of cohabitation has already been taking place. In a little less than an hour I see red squirrels, hooded crows, Eurasian jays and foxes all making use of the site, as well as various insect and mollusc species that I can’t readily identify. The surface of the building is also already becoming colonised by moss and lichen. Something slimy and green coats the prefab concrete panels. Plant life is particularly abundant; the floor coated with acorns and other seeds, and much of the site covered with a thick growth that has come into place in the years the site has been left to its own devices.

On a bench towards the back of the site Roberta and Jonas talk me through their proposed designs. b+’s original plans centred on flipping the bulk of the building’s prefab concrete slab panelling by 90 degrees to open significant portions of the interior to daylight. The resulting exterior space would be used to create walled garden habitats. In addition to this move, the basement level would be backfilled with earth and the surrounding concrete terraces would be permeated to allow for plant growth. This proposal estimated that around 10 per cent of the building could be given over to non-human life.

When reviewing the plans, the Heritage Authority felt that the original proposal of flipping the concrete panels would significantly alter the legibility and distinctive rhythm of the building’s facade and so it was vetoed. This aesthetic constraint has pushed their proposal into a surprising new direction, which may allow for nearly half the building being offered up to non-human life.

For a space to be deemed fit for human occupation under German planning law, a number of key criteria need to be met: ‘You need access to a certain amount of daylight, you need to have ceilings that are a certain height, you need to be within a certain distance of staircases,’ explains Roberta. ‘So, what we did, is kind of map things out to figure out which spaces – with little to no architectural intervention – would still fulfil the criteria for human occupation and through that we got to about 50/50. This is a coincidence, but a nice coincidence.’

The 50/50 study was presented to the heritage authority in the spring of this year and – to the pleasant surprise of the b+ team – it was met with a positive response. They have spent the following months refining the plan and responding to feedback ahead of another roundtable meeting due to take place in November. All going well, this next round of meetings would see the proposal officially stamped and green-lighted; effectively pre-approved for whenever the thorny issue of ownership and funding is resolved.

The 50/50 plans resemble a complex jigsaw-like arrangement, with human space and non-human space interlocking with one another. Although they use the term ‘cohabitation’, the distinct parts would be strictly separate from each other. This is partly to give non-human life as much protection and autonomy as possible. Things would be free to come and go from the non-human space as they please, adapting it to their needs over time.

Where the human areas will comprise subsidised artist studios and cultural spaces, the question of what exactly ‘non-human space’ constitutes is still open for discussion and is one of the most conceptually interesting elements of the study. Rather than pre-emptively deciding on standard ‘plug and play’ greening measures (a provision of bat boxes or bee bricks, say), b+ are more interested in broader moves that will help define the potential usage of this space on legal and programmatic levels.

‘We were thinking, what happens legally if you designate parts of your building as nature?’ says Jonas. ‘You don’t submit plans for it. You just effectively delete it, or scoop it out from your plans and define it as exterior space.’

This would both exploit planning loopholes that would better protect the space and give more freedom with regards to what goes on there, but it would also serve as a rhetorical device, to help move beyond discussions about whether it is acceptable to leave such large portions of a building effectively unoccupied and ‘unproductive’.

‘You don’t ask me what’s happening here, nor what I am programming here,’ Roberta points at the blank white exterior space outside the building plan. ‘You don’t even think about it. So we’re basically imagining that this exterior space and the non-human interior space are the same, at least legally, if not also physically. It could have a landscape architect come in, or it could be left as is, but the idea that it is part of the floor plan of a building and therefore needs to have a specific function gets removed from the equation.’

b+ are keen to avoid narrow or overly romanticised visions of what multispecies cohabitation constitutes, or what kinds of co-inhabitants are valued, approaching with what seems to be characteristic cautiousness. ‘Do you create new openings in the walls or remove all the interior doors? Do you “prime” the space in some way, and if so why, and who for?’ says Jonas. ‘How do you avoid subconsciously making decisions that just benefit things like foxes and squirrels because they’re mammals and we can relate to them more than we might to insects or snails or plants or worms and fungi? One thing we are thinking about is creating a glossary of terms, or glossary of perspectives. Because you might look at it from a certain scale or perspective and realise, “Oh, the building is thriving.”’

Indeed, a recent study of the biofilm currently growing on the undisturbed surface of the Mäusebunker’s exposed concrete facade by researchers at the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und-prüfung (Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing) found it to be characterised by a notably high diversity of bacteria, fungi and algae species. 4 Julia von Werder and Alexander Bartolomäus, “Analyses of the Biodiversity of Biofilms on the Façade of the Mäusebunker” in Mäusebunker and Hygieneinstitut Two Berlin Brutalist Icons, ed. Ludwig Heimbach (Berlin: Jovis Verlag, 2024), 375–78.

They quickly run through a number of other theoretical possibilities and challenges that range from whether or not the non-human space should be deemed a protected landscape and cut off from human access altogether, to whether they could draw up a framework in which non-human life becomes a legal tenant of the building with an enshrined set of rights. They reference the Austrian architect and artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser whose ‘tree tenants’ were treated as shared owners of his 1985 Hundertwasserhaus apartment building in Vienna. 5 An extensive archive of Hundertwasser’s writings on tree tenants and other topics ranging from the aesthetics of mouldiness and the political potential of eating nettles are available at: https://hundertwasser.com/en/texts/original_texts_and_manifestos

If the list of possibilities and considerations seems vast, almost sprawling, that is partly the point. For the time being b+ are happy to speculate until they know exactly what the parameters are. ‘If it’s a question of how we, as architects, design for nature. I don’t think we’re equipped to answer those questions alone,’ says Roberta, before drawing the analogy of structural engineers and the importance of architects collaborating with people who have expertise outside their own. The intention is to eventually set up a committee of wider collaborators with expertise spanning ecology and law, as well as organisations working at the forefront of human–nonhuman relations, such as Organism Democracy, who facilitate participatory democratic councils aimed at granting agency to non-human entities, and terra0, who have used blockchain technology to create a model for forests to be able to effectively own and govern themselves.

The proposal works much like a weed might, seeking out the gaps and opportunities within the awkward parameters in which it finds itself.

But before any of that comes the nuts and bolts work of securing the relevant planning permissions, and of finding a willing developer for the site. Following my visit, I speak to Ludwig Heimbach, a researcher and architect who has been involved in the campaign to save the building and whose recent book Mäusebunker and Hygieneinstitut (2023) documents both the history of the building and the ensuing efforts to both preserve and find a new use for it. He describes the building as being stuck between a number of possible development outcomes, ranging from private investment to public ownership, although he fears Mäusebunker may remain stuck in bureaucratic indecision, becoming yet another of Berlin’s ‘sleeping giants’, like the Tempelhof Airport, Diesterweg School and the Internationales Congress Centrum.

As an external observer, there still seems to be a lot of precariousness in the project. b+ are not attached in any legally binding sense, and their work on the study remains pro bono and speculative. It is still entirely possible that when a developer does eventually enter the picture (if at all), they might arrive with very different ideas around how they think the Mäusebunker should be used. But when I put this to the b+ team they appear quietly confident, reasoning that there is a certain protection afforded by the awkwardness of the site, and that legislation forbidding listed buildings from sitting empty and draining taxpayer’s money will prevent it remaining unoccupied for too long. Perhaps they even have a trick up their sleeve: in April 2021 the practice’s founder Arno Brandlhuber submitted a formal purchase offer to Berlin’s mayor, in partnership with the German art collector Johann König, in which they proposed to buy the site for just over 2.8 million euros. The deal ultimately didn’t land, but the offer technically still stands. 6 Ludwig Heimbach, “The Debate: A Social Experiment” in Mäusebunker and Hygieneinstitut Two Berlin Brutalist Icons, ed. Ludwig Heimbach (Berlin: Jovis Verlag, 2024), 321–36.

It will be interesting to see how the project continues to unfold and take shape. Architectural work engaging critically with non-human life and multispecies cohabitation is increasingly common in educational and conceptual spaces, but remains vanishingly rare in practice. For all its conceptual intrigue, if this project is to be realised it will be because of its willingness to engage with practical, almost prosaic realities, alongside the more attention-grabbing high-concept work. And perhaps this is the real magic of the Mäusebunker proposal; what might be called a healthy balance of pragmatism and narrative flair.

From the outset b+ have sought to ground their study in the existing legal, political and economic realities, while using them to their advantage. In doing so they ensure that their project has the best possible chance of coming to fruition. But also, crucially, they suggest a way of actively redefining what is possible within these existing hegemonies. The proposal works much like a weed might, seeking out the gaps and opportunities within the awkward parameters in which it finds itself.

Whether or not it is ultimately successful, the Mäusebunker proposal is a much needed attempt to move ambitious, non-human-centred projects away from being viewed as purely speculative ventures to something seen as a viable possibility. A way of arguing, and to a certain extent even demonstrating, that it is possible to bridge the gap between theory and practice, which can so often seem insurmountable. In this light, the project might be viewed as part of a much broader web of rhetoric and persuasion. One that frames the consideration of non-human life as a crucial part of how architecture grapples with its place within a wider, non-negotiable ecological context.

Who knows how long the current financial and legal wrangling will go on for, and what will happen after it is resolved. Until then, the Mäusebunker continues to sit empty, of human life at least.