Lo-Fab

For MASS Design Group, constructing a building means thinking through land, materials and craft across a bioregion. A new campus for conservation agriculture in Bugesera, south-east Rwanda demonstrates their particular approach

What can a building do? For MASS Design Group – a non-profit architectural firm of more than 130 employees with headquarters in Kigali and Boston – ‘buildings must heal’. Speaking from Kigali, Christian Benimana, who leads MASS’s Africa Studio, refers not simply to designing buildings which sooth their inhabitants, but to building processes that restore people’s relationships with their environments. To facilitate this, the firm has developed a design approach – some even call it a ‘movement’ – known as Lo-Fab. 1 ‘The Power of the Lo-Fab (Locally Fabricated) Movement: In Conversation with Andrew Brose of MASS Design Group’, Material Driven, May 2016; John Hill, ‘The Lo-Fab Movement’, World-Architects, May 2015; ‘The Lo-Fab Movement 2015 Campaign: How we build, and who builds, matters’ Archidatum, May 2015.

At its most basic, Lo-Fab is a model for local fabrication anchored in bioregions. Its core principles, as developed by MASS, are to hire locally, source regionally, train where you can and invest in human dignity. It is this final principle of ‘human dignity’ that propels Lo-Fab from supply chain management into a proposition for reorganising society at large. Dignity here speaks of our universal human rights; to live in a sustainable environment, to have access to a flourishing life. 2 Pablo Gilabert, ‘Understanding Human Dignity in Human Rights’ in Human Dignity and Human Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018, 113. MASS projects begin by asking: who lives here, how do they build, what materials and skills are abundant in this landscape? The construction materials and methods for a project are then drawn from the specifics of a place and its people. This results not only in a physical building, but a network of bioregional livelihoods bound together around a structure. The success of Lo-Fab is measured using MASS’s design metric of handprint/footprint which weighs minimised carbon footprint against maximised hand-built materials and methods – be that in the context of Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) or the United States.

Lo-Fab generates rooted supply chains that are low-impact, adaptable and regenerative

For Benimana, practising amid a climate crisis and in the shadow of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, Lo-Fab offers a sustainable model of repair for infrastructural and social systems in the country. In place of an imported product catalogue of materials and suppliers, Lo-Fab generates rooted supply chains that are low-impact, adaptable and regenerative. As an example, MASS’s Butaro District Hospital in Rwanda (2011) was built with materials including volcanic rock from the surrounding Virunga mountains; the stones were shaped and laid by Butaro masons. This unconventional construction technique using locally abundant and readily renewable materials and skills is now key to the local economy. According to MASS fellow Lydia Kanakulya, ‘When you look at a MASS building, you see a display of possibility. The traditional materials and crafts that make up its textures are our future industries in this area.’ 3 Lydia Kanakulya, MASS African Design Centre fellow (2016–18), interview with the author, 2020.

MASS’s building for the Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture (RICA), completed in 2023, is an evolution of Lo-Fab’s restorative agenda. The scope has now extended from repairing social and infrastructural systems within an environment to include restoring the environment itself. RICA has been set up to rehabilitate the once-fertile farmlands on the shores of Lake Kilimbi in Bugesera, south-east Rwanda, which are threatened by over-farming. These lands are part of the verdant forest and savannah belt that makes up the Victoria Basin bioregion in the Equatorial Afrotropics – a bioregion centred on Lake Victoria and stretching across Uganda, eastern Rwanda and into parts of Tanzania, Burundi, the DRC and Kenya. 4 Bioregion as described and delineated by One Earth. https://www.oneearth.org/bioregions Through its promotion of conservation agriculture, a practice that ‘repairs rather than destroys a landscape’ 5 Institute for Conservation Agriculture. Source , the institute will support subsistence farming families who have inhabited the region for generations, training the next generation of agricultural entrepreneurs.

The 13.7 km2 site hosts 69 buildings including academic facilities, housing and agricultural storage units. It co-exists alongside papyrus wetlands and one of the very few intact remnants of savannah forest in Rwanda. Over recent decades, deforestation and agricultural clearing have driven the forest further away from the wetlands. Where a woodland-wetland connection had historically allowed for migration of flora and fauna, the local biome is now fragmented. RICA’s landscape design tries to heal the landscape by stitching the isolated woodland back to the lake with new ‘landscape corridors’, created by planting over 300,000 plants, propagated from plant material collected on-site. 6 Katherine Logan, ‘MASS Design Group Establishes a Model for Regenerative Construction in Rwanda’, Architectural Record, 1 August 2022. These corridors allow species and ecological processes to once again move across ecosystems, encouraging biodiversity. 7 Luca Palmeri, Alberto Barausse, and Sven Erik Jorgensen, Ecological Processes Handbook. Florida: CRC Press, 2017, 341. Embedded within this landscape, a series of small farming fields serve as land-based studios for experimentation with regenerative and agroforestry farming practices.

The campus buildings themselves are almost entirely earth-based: stone for the foundations, rammed-earth and compressed earth stabilized blocks (CESBs) for the walls and terracotta for the roof tiles. This is both in poetic reference to the centrality of soil in conservation architecture and a result of applying Lo-Fab constraints to the build. The kinds of materials best suited to bioregional production in the area are stone from two neighbouring rock quarries and earth from the less fertile hilltops surrounding the site. Clay is sourced from the Nyabarongo river 65km north of the site. Individual artisans and small co-operatives process these materials with the aim of building domestic structures or household and touristic objects. The height and size requirements of RICA’s buildings, however, demanded that these skills be enhanced significantly; and in the case of pottery studios, expanded to include tile production. To complete the project, over 295 artisans were trained as part of the Lo-Fab construction. By harvesting much of the project’s materials from the site and its immediate surrounds, its embodied impact was reduced to 40 per cent of a business-as-usual approach. 8 Kelly Alvarez Doran and James Kitchin, ‘Footprint, Handprint: Pursuing Regenerative Architecture in Rwanda’ in The Regenerative Materials Movement. Portland, OR: Ecotone Publishing, 2023, 182.

Entering the earthen buildings of RICA, one finds over 9000 objects, from furniture to fittings, that have been produced using the Lo-Fab approach. The Kayonza Lounge, named after a neighbouring district, is one such object. Reminiscent of a club chair, with its deep seat and distinctive low back, the Kayonza is designed as a resting place for students and has two primary components: a woven backrest and wooden structure.

The woven backrest was produced by the Teruga co-operative, a group of women who use banana fibres – a principal agricultural waste product in the area – to produce high-quality woven products; in collaboration with Iriza Ntako studio who weave from sisal, made from the agave plant which grows wild throughout Rwanda. The skills of the accomplished weavers in this area, described as one of ‘the world’s most refined achievements in basketry’, 9 Tom Phillips, Africa: The Art of a Continent. London: Prestel, 1999. had previously been used to produce ten-dollar objects to sell to tourists visiting the Akagera National Park. These craftswomen worked with MASS to reposition themselves as suppliers of architectural and design materials for the thriving construction industry in Rwanda. 10 Christian Benimana, Co-Executive Director and Senior Principal of MASS Rwanda, interview with the author, 2020. According to an on-site weaver, Souzane Murekatete:

With MASS, we came out of our comfort zone. I used to understand that dried banana leaves were just a cooking fuel until I met the right craft person. Now our banana weave and sisal processes are combined. This shift requires not only the adaption of the crafter but a modification of the craft itself.

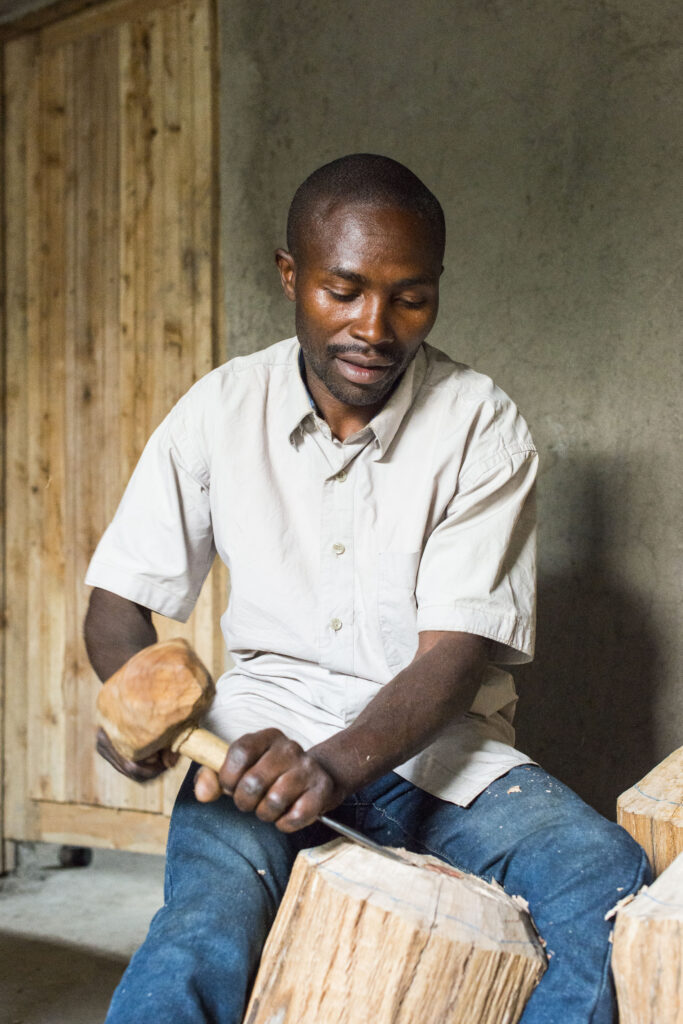

The wooden structure of the chair drew on the skills of carpenters based on the shores of Lake Kilimbi, directly opposite to the RICA campus. While the skills were largely in place, the chair required quantities and strengths of wood that were not available in Bugesera. MASS worked with foresters across the bioregion – extending into neighbouring Tanzania – to source endemic trees such as the Markhamia lutea, known locally as the Musambya. The timber from this tree had primarily been used as firewood and for charcoal production in the region; now its lightweight characteristics were applied to the design of the Kayonza Lounge. This adaptation introduced new construction techniques into the local woodworking industry and helped to rehabilitate the timber market, which was commonly regarded in the region as ‘not modern’. 11 Christelle Muhimpundu, Senior Designer MASS.Made, interview with the author, 2024. These wooden structures and the woven chair backrests were assembled on-site by ‘MASS.Made’, the furniture division of MASS Rwanda.

Through objects such as this, the RICA site has become the nexus for a network of bioregional practices. In contrast to short-lived items like imported plastic chairs, objects like the Kayonza Lounge can now be built, maintained and repaired by artisans within the region – a principle that is true of the campus more broadly. It took over 800 people to build and fit-out the RICA campus, 90 per cent of whom live in the surrounding Bugasera district. 12 Kelly Alvarez Doran and James Kitchin, ‘Footprint, Handprint: Pursuing Regenerative Architecture in Rwanda’ in The Regenerative Materials Movement. Portland, OR: Ecotone Publishing, 2023, 190. In the words of MASS fellow Tshepo Makholo, ‘We wanted the community who built this school, the hands that cut the rock and fired the tiles be able to adapt the project, build on it after our departure.’ 13 Tshepo Mokholo, MASS African Design Centre fellow (2016–18), interview with the author, 2020. RICA stands as a new precedent for what a radically contextual mode of practice can do socially, materially and ecologically. By rooting a project within a landscape and its communities, ‘projects move beyond just issues of energy use and efficiency, to holistically design the project ecosystem, including an entire supply chain that is sustainable, resilient, and regenerative’. 14 MASS Design Group. Source

In the Lo-Fab framework then, bioregions are sites of intervention for restorative action. The philosopher Dani Wadada Nabudere in his Restorative Epistemology advocated for African-based problem-solving rooted in the resources and skills of places. 15 Dani Wadada Nabudere, Afrikology and transdisciplinarity: A restorative epistemology. Oxford: African Books Collective, 2012. For him, communities are ‘depositories of indigenous knowledge and nurseries for alternative [design] solutions’. 16 Ronald Elly Wanda, ‘Afrikology and community: Restorative cultural practices in East Africa’ in Journal of Pan African Studies, 6.6, 2013, 7. In the work of Nabudere and Benimana, bioregions are mobilised as part of a post-development agenda, which views development as Eurocentric and based on Western models of ‘modern’ industrialisation that are largely unsustainable and ignorant to the local contexts to which they are applied. This is especially pertinent in a world where climate response may well be best conceived and delivered by local inhabitants rather than international treaties. In the words of Benimana:

We are not trying to help people to build projects in Africa – that is not what we are trying to do here. We are trying to figure out how to build ground-breaking, globally relevant projects within the context of Africa. Projects that remedy our relationships to the places we live, and rehabilitate the design professions in which we practice. 17 Christian Benimana, Co-Executive Director and Senior Principal of MASS Rwanda, interview with the author, 2024.